702CE - 1057CE: The Dark AgesIn 702CE the Disunited Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Wales had five million subjects, produced more food, goods and wealth than any other set of countries in the known world, held more than than any other and an English middle class citizen could expect to live to 70 years of age, be fairly wealthy and fairly unhappy as well. Of the five million people in the Disunited Kingdoms, 1.6 million lived in London, 820,000 in Edinburgh (formerly Caledonium) and 800,000 in Cardiff (formerly Ambianum).

King George II of the House of Pendragon inherited a mess of a kingdom. Corruption was rife, especially in the colonial provinces in Africa, and attempting to keep control cost an inordinate amount of money even before the bribes and embezzlement were considered. As a result, taxation was criminally high at more than half of income, with no money spent towards public works or counter-espionage and only a pittance left free as disposable income for the middle classes. Furthermore, centuries of warfare had taken enough of a toll on the economy that even as victors the effects of war exhaustion were being felt in the more populous cities. Fortunately, unlike his court George recognised that Chancellor Picasso had little to do with these burdensome costs and so retained him as a trusted advisor.

In 713CE, as King George was busy cracking down on corruption throughout his realm, Prince Asoka IV of Bombay travelled to London personally along with his court and was received as a most honoured guest with a sumptuous feast. The day after, Asoka knelt before George, along with his court.

O wise and benevolent king of England and Africa, thy reach is without limit, thy grasp irresistable. Long have thy people shielded mine from the threat of Carthage and now they quiver at thy presence. Thou art strong, majesty, and we are not so strong as thee. Let us shelter behind thy strength, let our enemies know that they are thine enemies also, and we shall bend the knee to thee in loyalty everlasting.

With this offer of vassalage came one of the few major decisions of state upon which King George and Chancellor Picasso could not agree. Picasso made it clear that the burden of supporting a vassal state would have ruinous effects upon the economy, that it might kill an already crippled system, but George had his eye upon destiny. A staunch Confucianist, King George held a belief that England had a manifest destiny to bring the world under Victory's (and its) care. He over-ruled Picasso and accepted Asoka's offer to bend the knee. Asoka swore to obey and honour his liege, and to adopt the word of Confucius in lieu of Hinduism.

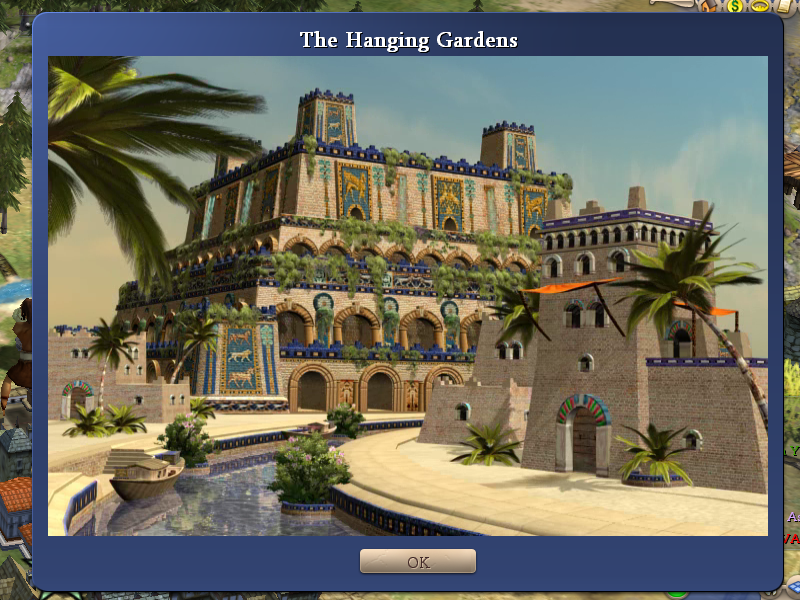

To celebrate the new Duchy of India and England's status as a colonial power, plants from all across Britain and Indo-Africa were brought to London, from the deep jungles of Hadrumetum to the cold tundra of south West Anglia. They were housed in a vast and elaborate series of gardens, built into a wide amphitheatre, almost the inverse of the classical pyramid barrows of the ancient Britons, with an artificial lake in the centre. Trees stood on raised avenues, plants hanging in baskets in archways. The Hanging Gardens were beautiful at their inception and current estimates put them as needing over 300 tonnes of water a day to sustain all their verdancy.

[Double edged sword here. The Hanging Gardens give a one-off boost of +1 pop in all cities and a permanent +1 health bonus to keep them going. It doesn't increase happiness, however, which is part of my reason for accepting Asoka's vassalage. Vassals give you a +1 imperialism happiness bonus to all your cities (and take a -1 imperialism penalty, but who cares about them?), at the cost of increased gold in maintenance. They also join your wars and are happy to take your deals, so it's pretty nice.]

Six months after Duke Asoka swore his fealty, King-in-exile Hannibal of Carthage arrived under armed guard at King George's court. He brought with his maps of Punic lands, a chest of silver and the offer of the port town of Sicca (next on King George's list of targets) along with his oath of vassalage if George would but spare his people. Satisfied, George accepted his vassalage; King Hannibal of Carthage bent the knee and arose Duke Hannibal of Northern Africa. Carthage, of course, would stay in English hands.

The Punic Wars, at long, long last, were at an end.

[The funny thing is, this was actually Hannibal's suggestion. I was going to see if I could peace out for Sicca, but I wanted to see what he would give me and he offered me what I wanted anyway plus abject servitude. Of course, my economy is now in the toilet but I should be able to recover from this regardless. A slightly frustrating side effect is that because so many people hated Hannibal they are all suffering a -1 relations penalty with me now that he's my vassal.]

In 722CE, as proof of their allegiance, Indian colonists settled the land bridge between London and Cantiacum, swiftly converting to Confucianism.

[What.]

By 724CE, Chancellor Pablo Picasso had acquired the lung cancer that would soon kill him. Furthermore, at 89 years of age he knew that his time would soon be coming regardless. Taking advantage of his patron's own increased age (for decrepitude strikes some earlier than others), in his final years Picasso began an overhaul of the English government that would completely change how the country was run. Up until Picasso's time, Parliament was simply an assembly of the various Earls and Barons of the country (now including representatives of the two Duchies) that came together when the king's Council wished to announce changes, typically tax increases, for the Lords to adhere to. Government was actually run by the Council, a smaller assembly of the most politically active and favoured Earls who served to represent their lands and who decided upon policy.

Picasso began by arranging for more members of the minor nobility to have bureaucratic positions within government, entrenching them into the civil service. These Barons had an excuse to observe Council, which permitted Picasso to extend council sessions into full Parliaments. Then Picasso began employing members of the middle classes as civil servants, taking advantage of an increased political awareness amongst the professional class. Finally, once Parliament had been established as a regular occurence, Picasso instituted a second Chamber of Parliament, intended to advise the first. This House of Commons was drawn of wealthy individuals delineated by geographical region, appointed by the King 'upon advisement' of local elections of those who could afford to stand. Picasso then made it a requirement for both

houses to agree upon laws before they could be passed.

This may seem incredible, but Picasso's work took ten years and killed him and was almost certainly accompanied by vast bribes, blackmail and in all probability outright imprisonment and murder. Additionally we must consider that there must have been existing sentiment that would have made such broad changes possible. Additionally, the qualifications for voting for a member of the House of Commons were still restricted to males over thirty with stringent property requirements. Nevertheless, this was the closest Britain would get to universal suffrage for centuries.

Picasso died in 734CE. If he had further ambitions for reform, they never came to pass. King George passed away two years later, leaving a young Prince Uther (George's grandson, for Princess Anne his daughter had died in childbirth) to inherit a throne limited by the wishes of Parliament and restricted by the machine of bureaucracy. The economic liberty provided by a freer suffrage was welcome to many, and although many criticised the reduction of the importance of the feudal structure the bureaucracy did provide great boons of wealth in the capital - which under King George's reign might have been enough to counteract the government's growing debt. Unfortunately, with both George and Picasso dead, the 14-year-old King Uther lacked for true guidance. In the end, he was simply not as capable an administrator as his father or his father's advisor, and the kingdom fell swiftly towards ruin.

[Last turn of the Golden Age, so I re-jigged government to be Universal Suffrage, Bureaucracy, Caste System, Organised Religion and a decentralised economy because we don't have any valid Economic civics. We dropped Representation, which will hit us more in the bonus beakers than the happiness loss, and we dropped Vassalage because as it turns out we were below our free unit supply anyway. The bonus capital income from Bureaucracy more than makes up for any loss there. The real killer is the simple fact that our Golden Age is over. Now we return to a standard economy.]

Uther's primary concern was the kingdom's crippling debt and how to resolve it. He began by employing the newly-enfranchised middle classes; the expansion of the franchise had extended the economic freedom of the professional class and their ability to gather resources and employ labour. With this in mind, Uther put forward what might be considered the first true public works contract; in exchange for a frightening amount of gold from the Utican mines, a consortium of merchants and tradesmen agreed to pool their resources and complete construction of a courthouse in Kerkouane, as well as hiring and putting together a necessary legal staff to run it, within five years. Such matters usually took decades to achieve, so the king considered it to be an acceptable use of wealth. Unfortunately, such extravagant expenditures put the treasury in short-term debts, despite the long-term benefits of reduced corruption (and thus higher taxes and less bribery) in Kerkouane. So Uther permitted the services of the realm's finest playwright, Cecil Tourner, to be given to the Malinese in exchange for over four hundred pounds of silver. The Malinese experienced a golden age of drama, whilst Uther had enough wealth to finance further expansion.

Alexander Neckam is credited for the first magnetised needle compass in England, produced in 742CE. A development of the lodestone, the compass made navigation significantly easier, permitting one to find one's direction in unfamiliar lands without the aid of the stars or the sun. The compass created a keen interest in exploration amongst those of the wealthier classes.

In 762, the Ethiopians requested the formal aid of the English in their war against the Zulus. Given the lack of proximity to Ethiopia, this 'war' seemed to be nothing more than a show of support for the Malinese, who were in a rather hotter war for Zululand. The 26 year old monarch, who was no general or strategist as his father was, believed that he could only nominally involve himself in the war, sending over the strong militaries left over from the conquest of the Carthaginians for some quick, non-territorial battles for the sake of glory and profit. Additionally, it seemed, he hoped that by placated a well-armed enemy nearby it might give him time to prepare.

In the latter half of the eighth century, the Ethiopians built a great bronze colossus over the Bay of Aksum, to welcome ships to trade with them.

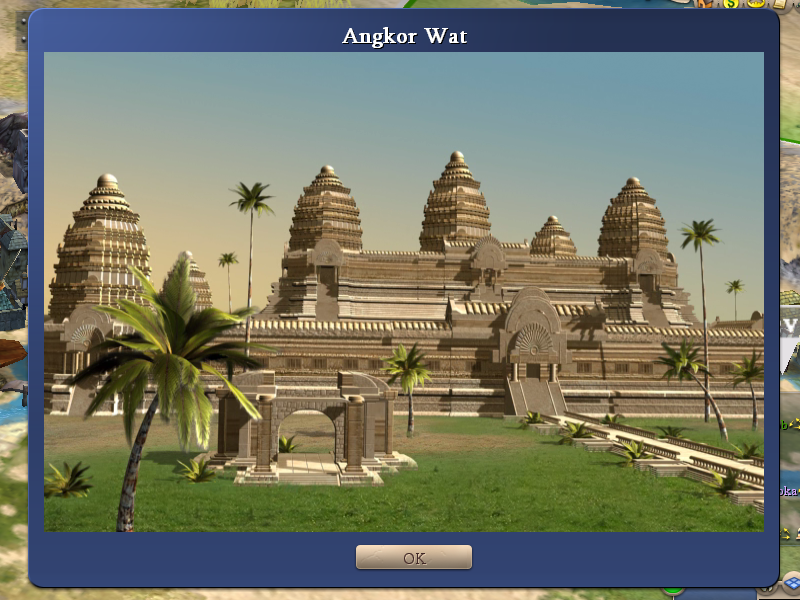

In 796, King Ruidri of Wales laid the final stone upon Angkor Wat, a great temple to Victory in Cardiff. Ruidri was well-known to be a pious man, but he was also known for his rivalry with Uther. Ruidri opened the borders of Wales to the Ethiopians (and thus indirectly to England and Scotland, who shared open borders with Wales) and also set about the great construction of Angkor Wat, quite possibly to one-up the Colossus of Aksum and also to show himself more prosperous than Uther, who had been spending bis entire reign trying to stabilise the crashing economy of England and would continue to do so until the day of his death.

[Agkor Wat is useful. Every priest produces an extra hammer; 2 hammers and 1 gold, which makes them better than engineers except for the Great Person production. We have temples across the empire, so they are a welcome bonus.

On a more meta note, I have been doing a little reading on 'deficit research', which posits that moving the research slider up and down simply adjusts gold-to-beaker production along a stable ratio; in other words, putting the slider at 0% for ten turns and then 100% for ten turns produces the same amount of beakers as putting it on 50% for twenty turns, so long as the ratio did not change in the intervening period.

Our ratio is 1:1.18, which means that any gold we earn is 1.18x as valuable as any beakers we earn, in terms of gold spent on the slider (i.e. 1 gold translates to 1.18 beakers). In practical terms, this means that on average across our entire empire we have an 18% Research bonus compared to our Gold bonus. In some areas, such as London (Academy + Library) this is higher than the average, so this is a good place to leave commerce as is, or perhaps devote some population to scientists. In Edinburgh, where we have a market but no library, gold efficiency is much higher - it makes sense to commit population to Merchants to take advantage of the bonus, where it would be commerce-neutral, as this gold is not affected by the science slider and so remains the same - and thus may be converted by deficit spending into more beakers.

This, at least, is my present understanding: in Edinburgh, my gold efficiency is 1.25 (market) and my beaker efficiency is 1 (no buildings). Let us imagine that I have 41 commerce here (I do, with no specialists). Now, 26 of this commerce comes from trade and tiles I cannot deselect, so let us imagine that we have 15 'free' commerce from water tiles to play with. This translates to 15 beakers (at 100% science, but effectively I would produce 17.7 using my average ratio) or 18.75 gold (at 0% science, because 25% market bonus). Let us imagine that I take all of those water tiles and make them into Merchants (some food loss, but net commerce is the same, just dedicated wealth). We now have 18.75 gold being produced regardless of the science slider.

The extra 3.75 gold is then converted at our default ratio by the rest of the realm (by the simple expedient of raising the science slider enough to spend it) into an additional 4.425 beakers. Where beaker efficiency is lower than average, it can be more efficient for us to switch out production directly to gold. I think. It's late and my thinking is fuzzy.]

In spite of the apparent promise of innovation in the early 8th century, the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries saw a Dark Age for the English; with a line of kings focused chiefly on stabilising their crumbling kingdom, high taxes and little intellectual freedom, the academia of the English stagnated almost entirely. A ray of light amidst this gloom was Renee Descartes, a philosopher whose meditations on the subject of the mind, soul and being started a philosophical school (the Cartesians) that would continue long after his death.

In 895, Earl Charles of West Anglia commissioned a set of statues commemorating the line of English kings since the Saxon Conquest, carved by the sculptor Moai of Ardsley. The Moai Statues served as an inspiration to the people of West Anglia, constructed in concentric rings surrounding Eppillus' Lighthouse, but during their commission Moai established several co-operative organisations of tradesmen, particularly those working along the English Channel. These organisations would persist, pooling their resources for great productivity for generations to come.

In 902 the Confucian scholar Dr. Sankore, an Indian philosopher who studied at the Academy in Utica, established his own College at the Academy in London with the blessing and sponsorship of King George IV. Classically, the Academy taught a structured series of lessons aimed at permitting one to pass governmental examinations, but attracted a semi-formal company of academics who made use of the Library and the facilities, as well as using it as a hub to keep in touch and share ideas. Sankore formalised large scale teacher-student relationships, employing learned scholars to act as professors and teach groups of students. There was not, at this time, such a thing as professors teaching individual subjects - a professor taught what he liked and only to the students who were part of his own, individual collegiate. The quality of education was very uneven, but it paved the way for future adaptations of the Academy.

In 917, Maussollos constructed his Mausoleum elsewhere in the world. Throughout the early 10th century, the long Dark Age began to reach an end; two centuries of harsh choices and parsimonious kings had stabilised the Kingdom of England and Africa and economic freedom was beginning to return to the realm. At the same time, adventurer companies operated in Zululand, conducting war not for conquest but glory and profit - Zulu villages and farmsteads were sacked and looted by the free companies of landless yeomen and frequently disgraced or opportunistic nobility.

In 953, King Aergol of Wales saw the completion of the Parthenon in Cardiff, an elaborate temple of imported marble, smaller but far more opulent than the temple it sought to outshine, Angkor Wat. Surrounded by marble columns, the Parthenon boasted an open roof onto a courtyard within, decked out in hundreds of statues and reliefs in honour of Victory. Like many such great works, the temple would continue to inspire individuals throughout the Disunited Kingdom for generations to come.

Meanwhile, in Aksum a re-organisation of Hinduism saw the rise of the Pope as a political force, ruling from the Apostolic Palace. A series of Ethiopian Popes would continue to influence global politics for the next hundred years.

The latter half of the 10th century saw a return to the traditions of innovation that had held in England before the Dark Ages. In 968, the first true telescope was invented, consisting of a pair of ground glass lenses. Combined with the compass of two centuries before, there began a revolution in seafaring, ships no longer bound by the coasts but able to risk passage across the high seas themselves.

[Finally, finally we can slide the research slider back up! It took two centuries of stockpiling wealth and rush-building Courthouses and Marketplaces, but we are back up to 50% Science and 331 beakers/turn. Let's do some catching up.]

Between 985-987, the Free Company of the Red Lion laid siege to the Zulu town of kwaDukuza, employing Welsh and West Anglian engineers to bring down the walls with their trebuchets. A modified form of the Godwin Doctrine followed, with the adventurers sacking the town for its value and leaving a ruin in its place. Amongst these free company members was the very successful commander Walter Raleigh, who returned home to England and purchased a knighthood with his wealth and commissioned the construction of a ship. Another such soldier was Baronet Geronimo (now a common war-cry amongst the war-gaming community) who took his years of experience in the field and devoted himself to a school of siege warfare in Cantiacum.

In 992, the Golden Hind

set out from the docks of Cantiacum, carrying ample supplies of food, water and some trade goods, as well as a stout and hardy crew and Sir Walter Raleigh himself. Sailing west, towards the setting sun, Sir Walter and his crew set about the business of seeking new lands beyond the reach of Africa.

In 1023, all of the wells in London were poisoned, with the perpetrators escaping uncontested. Whilst it seems likely from circumstantial evidence that the attack was carried out by Ethiopian agents, nothing was ever proved at the time. Nevertheless, the poison took decades to fully clear out of the water system, limiting London's growth and killing thousands.

The poisoning of London created a paranoid air, with little trust except amongst those of family or close friendship. Ironically, this paranoia helped the formation of true guilds, based off the designs of the Moai guilds in Cantiacum; individuals of the same craft joined together to pool their resources and set specific standards for their members to live up to. In effect, this formed an early form of quality control and greatly improved the quality and productivity of artisans who were part of a guild. The large workshops of Africa in particular strongly benefited.

Of note is the Butchers' Guild of London, which famously received accreditation from King George VI in 1036 for the superior cut of meat they produced in comparison to the average slaughterman. George granted the Butchers' Guild a letters patent giving them the exclusive right to cut meat for sale within London. Other Guilds soon found their ways into monopoly, and by the end of the 11th century there was not a noteworthy industry in any major British city not under the influence of a guild. The association of metalworkers also made it possible to engage in larger projects both labour and skill-intensive, such as the production of platemail armour from steel. If there was one downside to the guild system (which grew in time) it was that it restricted commerce to its own members, disadvantaging outside craftsmen and ultimately stifling innovation within their own craft.

At the same time as the guilds of England were forming, the Red Lion continued their assaults upon Zululand, capturing Nombaba.

In 1057, a small ship returned to African shores bearing crew members and news of the venerable Sir Walter Raleigh's expedition.

To His Highness King George VI, or whichever descendant of his sits upon the throne of England,

We have found land, although this news is now heavily out of date. We faced many trials during our voyage and were forced to stop for a long time at the Azores, those bleak western isles known to the Malinese. Eventually we reached a western land that was not merely fertile, but inhabited by men such as yourself and I! Alas, the Hind crashed upon our arrival, with the loss of our shipwright and his apprentice. We have remained the guests of the Americans, as they call themselves, for many years now, and it is only today that we see sight of our great ship being repaired. We have also constructed three smaller ships, sufficient we hope for the return journey. Those who wish to return shall carry these letters home, in the hopes that others may know our tale. I have taken a wife in my time here and shall remain, but for the continuing voyage of the Hind. My son shall captain her when the time comes, and I hope to live long enough for one last trip upon her boards.

Your servant,

Sir Walter RaleighContained alongside the letter was a detailed map of this new continent, America:

The continent of America is large, my lord, larger than Britain and Africa put together. The southern half is dominated by the Eastern and Western Americans, of which we have met the Eastern kingdom. North is the dominion of Russia, and further north still is the realm of Egypt. The Americas are vast, extremely developed and each nation is possessed of as much wealth and power as England itself. Most dangerously of all, they are each united under a single religion; Buddhism. Take care, my lord; America is a place of much wealth, prosperity and danger.

We are so screwed.

Author

Topic: Civ IV - Let's Try the British Empire: The Industrial Revolution (Read 17087 times)

Author

Topic: Civ IV - Let's Try the British Empire: The Industrial Revolution (Read 17087 times)