So I lost the original save, causing a temporary ragequit, but I didn't want to let this one lie. I restarted as before, but keyed in the wrong screenshot key, so all my shots up to about 260BC are non existent. Battle-wise, things went much as before - defeats at sea, crushing victories against insane odds on land.

After Cleomenes II (unlike his historical reign, he begins G:TP as an old man in his late 50s) took up the reins of the new Peloponnesian League, he began with the rather un-Spartan tactic of ruthless alliance forging. He forged trade based alliances with the Seleucids, Macedonians, Ponts, Carthaginians - virtually everyone on the borders of Greek states. Only the Romans declined, declaring war a year later.

Did Cleomenes expect these alliances to last? Did he expect any of them to come to his aid against Rome? Nike's wings, no. These bought him time - a couple of years for his 'allies' to strut around and pretend to be honourable before betraying him. These precious, utterly vital years were spent stockpiling resources and acquiring wealth for the essential task of bringing Athens into the alliance - eventually they accepted a 'fee' of more than eleven thousand denarii, and then only because the Macedonians were on their doorstep! Several rather forgettable battles and skirmishes followed against the Macedonians, who instantly betrayed the League. Pontus then betrayed the league and mounted ten years of completely ineffectual attacks on the Phrygian border forts. The Seleucids and Carthaginians cancelled their alliances apparently in preparation for attack, but then went to war with Pharaoh and Rome respectively. By the end of Cleomenes' reign Greece had no allies

and Rome, Macedon and Pontus as enemies. But by the gods were they ready for it.

A few intrepid Greeks face off against a mighty Macedonian horde; near two thousand in number. They have archers and worse still, two thirds of their entire force is cavalry. Reinforcements are delayed and even then they will match only a third of their force. But they have the upper ground.

A few intrepid Greeks face off against a mighty Macedonian horde; near two thousand in number. They have archers and worse still, two thirds of their entire force is cavalry. Reinforcements are delayed and even then they will match only a third of their force. But they have the upper ground. The battle progresses as reinforcements come into play. Taking the highest point on this side of the mountains, a line of Achaean phalangites hold against wave after wave of attacks. The general's Phrygian bodyguards take casualty after casualty, harrying the enemy at every turn.

The battle progresses as reinforcements come into play. Taking the highest point on this side of the mountains, a line of Achaean phalangites hold against wave after wave of attacks. The general's Phrygian bodyguards take casualty after casualty, harrying the enemy at every turn. Though the enemy is finally broken, the last hour of the battle is the bloodiest. Near half the Greek army routs or is killed butchering those Macedonians they can catch. Despite their best efforts, many escape.

Though the enemy is finally broken, the last hour of the battle is the bloodiest. Near half the Greek army routs or is killed butchering those Macedonians they can catch. Despite their best efforts, many escape. As usual, they expected to win. Though it cost them far more casualties than they would have liked... they did.

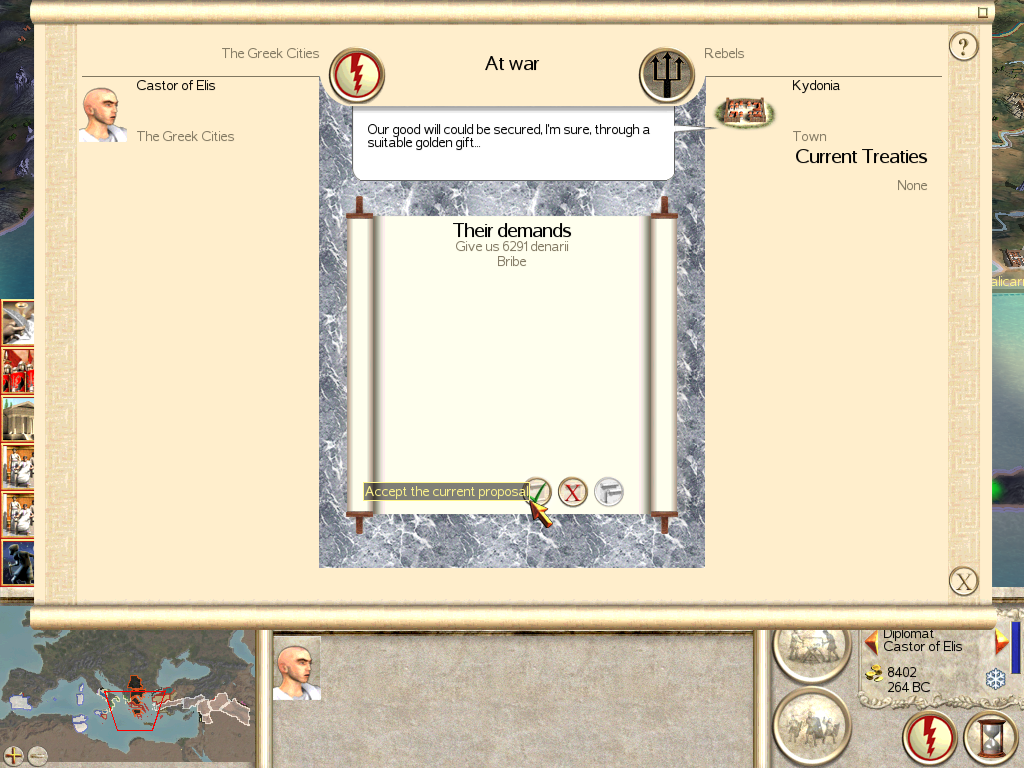

As usual, they expected to win. Though it cost them far more casualties than they would have liked... they did.This hefty investment soon paid off for Athens was a commercial powerhouse and brought in over six thousand denarii per year in grain, taxes and trade - the latter of which made up more than a third of the take. Other states followed suit; Crete, though it would be another six or seven years before the principal town Kydonia could support a decent set of docks to export the large quantities of purple available on the island's beaches.

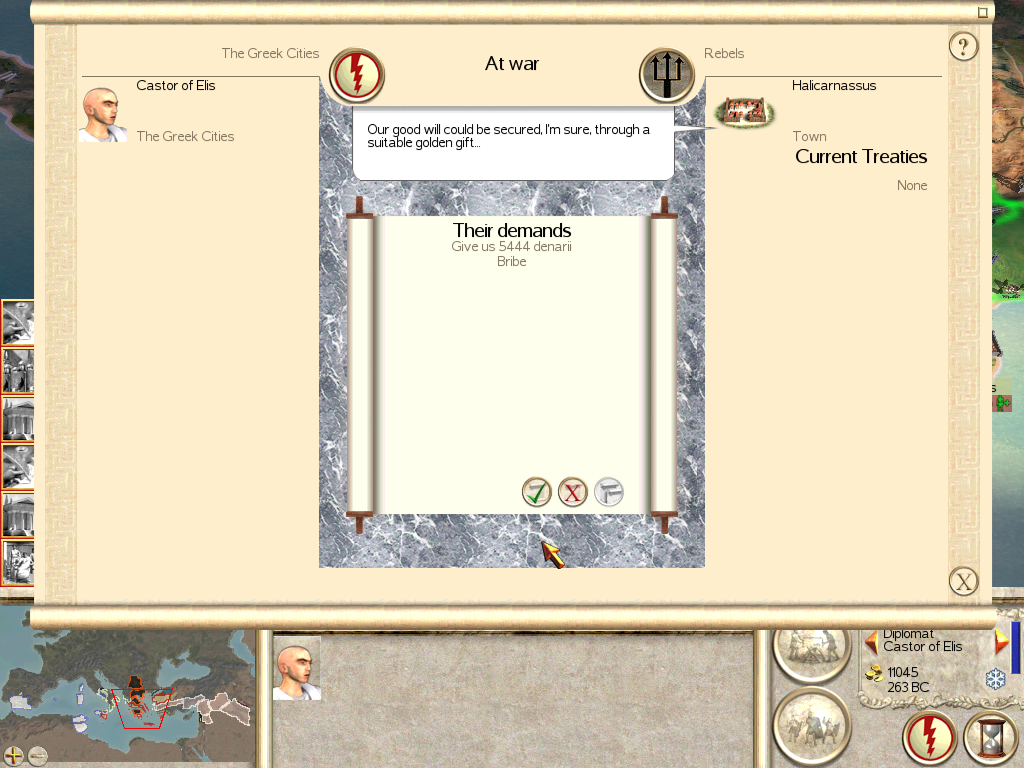

With growing Greek wealth, derived mainly from a growing and influential trade network spanning from Carthage to Byzantium and everywhere in between, more and more independent cities were willing to come under Greek protection. The sums were officially aimed at the 'betterment of the citizens', though naturally the vast majority disappeared into various patricians' pockets. Halicarnassus sided with Greece bringing with it the beautiful tomb of Mausolos, an inspiration to all Greek architects and builders.

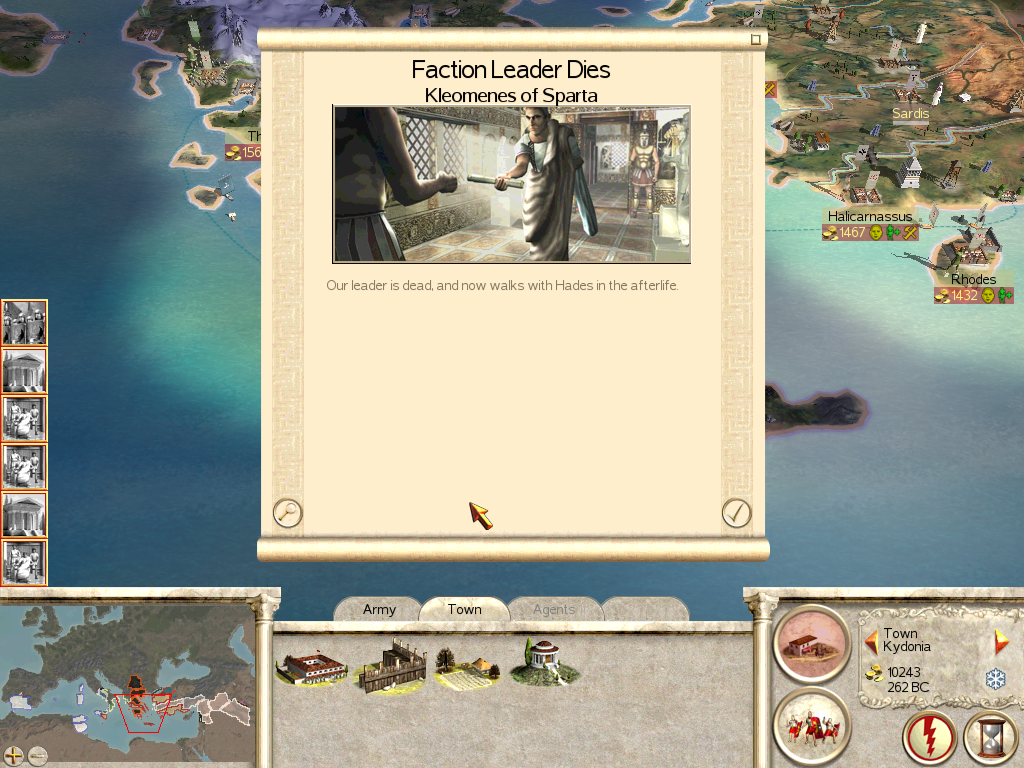

Cleomenes died after a mere eight and a half years ruling the League, of peaceful means - a very un-Spartan way to die, and as such was not remembered with a headstone. The last years of his reign were particularly fraught with Macedonian attacks on Athens where the sons of Alexander chiefly fielded massive and terribly equipped armies in the apparent belief that they had too many sons and needed to thin the herd. The Greeks proved to be exceedingly charitable in this respect.

Doros, his son, took over the League and continued to forge relations with neutral cities whilst battling a fairly stable Brutii threat perpetually trying to conquer Thermon and perpetually being stopped at one of the forts holding the northern passes down from their stronghold. To the west, the Scipii repeatedly assaulted the equivalent fortress north of Syracuse. Most of these battles were fairly trivial affairs where Greeks charitably did the best they could for the everpresent Roman housing crisis.

A rare battle against the Brutii where their forces were too large for the fort to reasonably handle. The local governor rode out to provide support with his Phrygian cavalrymen, aiming to take the hill point as in the Attican battle against the Macedonians.

A rare battle against the Brutii where their forces were too large for the fort to reasonably handle. The local governor rode out to provide support with his Phrygian cavalrymen, aiming to take the hill point as in the Attican battle against the Macedonians. The best laid scheme of mice and men often go askew. The Roman equites charged on ahead, hoping to flank the phalanx as they ran into position, swiftling finding themselves in a head on battle with the heavier Greek horses.

The best laid scheme of mice and men often go askew. The Roman equites charged on ahead, hoping to flank the phalanx as they ran into position, swiftling finding themselves in a head on battle with the heavier Greek horses. As usual, the governor's own men took the brunt of the assault, harrying and breaking the equites and hastati wherever possible. In this particularly awkward moment, the general is trapped alone amidst a horde of equites. His troops fought with such vigour and determination that the enemy surrounding him chose to break rather than deal a suitable devastating blow to their foes.

As usual, the governor's own men took the brunt of the assault, harrying and breaking the equites and hastati wherever possible. In this particularly awkward moment, the general is trapped alone amidst a horde of equites. His troops fought with such vigour and determination that the enemy surrounding him chose to break rather than deal a suitable devastating blow to their foes.

As so often is the case in these battles, struggle turned to rout, then to mopping up. A result of poor positioning cost the lives of several phalangites - though not harmed by a single enemy, arrows from behind thudded into their backs and slew them.

As so often is the case in these battles, struggle turned to rout, then to mopping up. A result of poor positioning cost the lives of several phalangites - though not harmed by a single enemy, arrows from behind thudded into their backs and slew them.

[This frigging farm. I see this farm a lot, because it is perpetually the place where the Scipii choose to make their stand. By the gods, Daimenos must have fantastically fertile fields with all the bodies we keep throwing into it.]

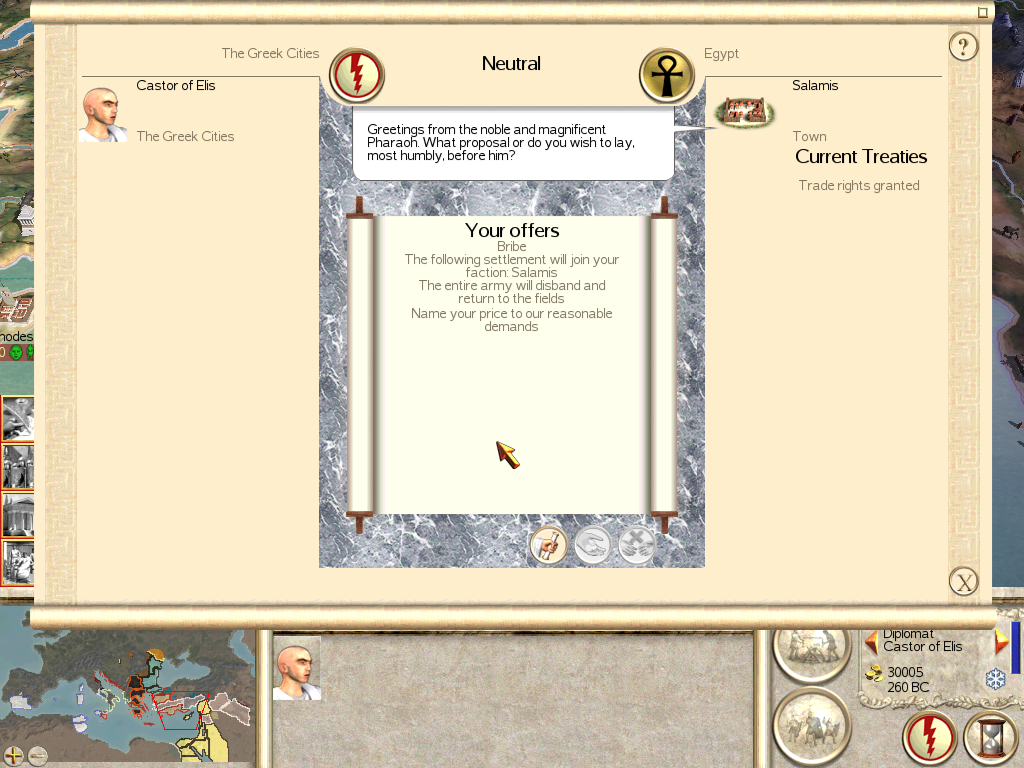

It is now 260BC, ten years into the League's existence. Greece controls Crete, Syracuse, Helicarnassus, Phyrigia, Attica (Athens), Laconia (Sparta), Rhodes and Thermon. This year our most incompetent diplomat (Castor of Elis, a man so utterly incompetent he has zero influence - he perpetually insults his hosts and often commits petty crimes, and the only reason I keep him is because I haven't the slightest idea how to fire him) decided to take a more risky foray. Travelling to the isle of Crete, he made contact with the governors of the town of Salamis. Despite insulting their sons, engaging in debauchery with their daughters and actually murdering three slaves out of spite, he negotiated a (cripplingly expensive) turn from the dominion of Pharaoh to the protection of the League.

As you can see, the League is doing rather well financially. Grain remains a primary source of wealth, along with tax, but note the Trade income. Quite often, factions neglect trade and this is somewhere around a thousand or less. Since most of my other income is eaten up on construction or upkeep, the heavy focus on trade and industry has effectively given us a turnover of 7000d/turn. This number will only grow the more markets and ports we build, and the best part is that right now all the cities (except Sparta, which rightly remains under the protection of Nike, goddess of Victory) worship Aphrodite. Once they convert to Hermetic worship, those numbers will go through the roof.

We are also getting sick of losing naval battles, but now that Syracuse has turned into a large city we can start building quinquiremes. In the Mediterranean, naval superiority is king.

Now that Sparta has finally built our first Agora, we can begin the real work - dispatching assassin after assassin to ruthlessly gut our enemies. As soon as their faction members die, we can move in our ludicrously wealthy diplomats and steal the city from under their feet.

Yes, it's a very Athenian way to wage war. But by the gods is it strangely satisfying.

Finally, the view of an outrider as one of Doros' sons goes on a pleasant ride through the brisk winter morning. On their way to murdering some Macedonians.

Finally, the view of an outrider as one of Doros' sons goes on a pleasant ride through the brisk winter morning. On their way to murdering some Macedonians.

Poll

Poll

Author

Topic: Let's Play Greece: Technical Pacifism! [Merchant Princes!] (Read 3413 times)

Author

Topic: Let's Play Greece: Technical Pacifism! [Merchant Princes!] (Read 3413 times)