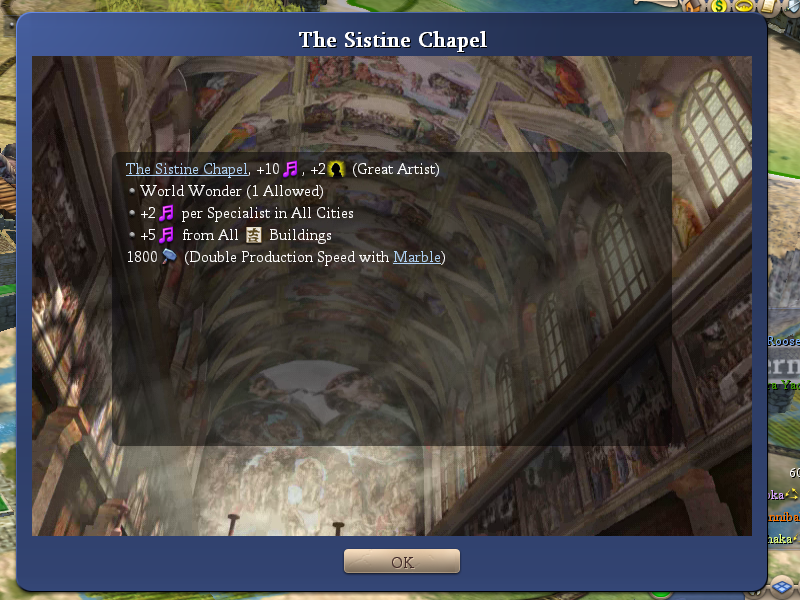

1352 - 1443: The Golden Age of Piracy In 1353, work by the Old Master Michaelangelo on the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel was completed. Located deep within Angkor Wat, the chapel served as the personal chapel of the Archbishop of Cardiff and once decorated boasted beautiful paintings of all manner of religious scenes; Creation; Victory blessing her chosen country; Confucius in lecture. The chapel provoked a lasting tradition of religious art in Confucianism thereafter.

In 1353, work by the Old Master Michaelangelo on the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel was completed. Located deep within Angkor Wat, the chapel served as the personal chapel of the Archbishop of Cardiff and once decorated boasted beautiful paintings of all manner of religious scenes; Creation; Victory blessing her chosen country; Confucius in lecture. The chapel provoked a lasting tradition of religious art in Confucianism thereafter.

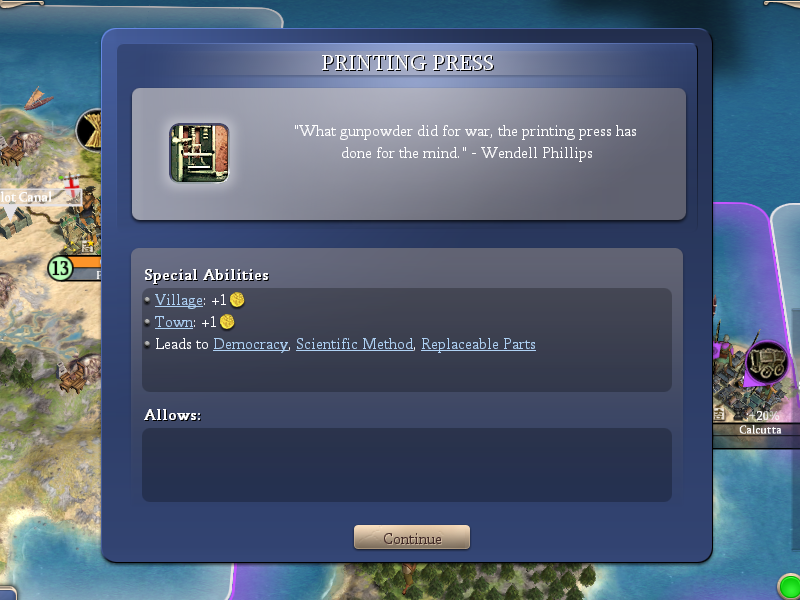

In 1368, John Gutenburg of York, Zululand, invented the movable-type printing press. Whilst block printing had existed since the sixth century, brought to Africa and thence Britain from Sumer, the movable-type press permitted one to draft up and print pages using the same machine by switching out die-cast metal keys with letters and numbers on, instead of laboriously carving out a wooden block with the desired text on to press. This made the production of books significantly easier, and also made the printing of cheap, disposable political pamphlets possible, where before such large quantities of print would have been ruinously expensive. As might be expected, the relative availablility of the written word created a great deal more demand for literacy and education. The extensive suburbs of some of the larger cities of the United Kingdom benefited in particular, where a significant middle class could take advantage of the press' bounty.

By 1376, the United Kingdom had a population of 34.5 million citizens, all at least nominally entitled to representation in the Houses of Parliament (so long as they were male, of a certain income, age and not criminal or insane). The capital, London, boasted just over five million inhabitants alone. The UK produced more goods, farmed more crops and made more money than any other nation, although their life expectancy was middling, given the size of their cities and lack of efficient plumbing or medicine, dissent was common in the colonies due to nationalist sentiment and the UK was a massive net importer of goods from other nations.

1376 also saw the beginning of the Golden Age of Piracy. Shortly after the ascendancy of Queen Elizabeth of the House of Pendragon, pirates began striking at Ethiopian shipping near Gondar, wrecking the whaling fleets that had operated along the coast since time immemorial. Within a few years, trade with Gondar, Lalibela and Aksum ground to a halt. Thanks to the proliferation of shipbuilding techniques, it became possible for wealthy individuals to purchase their own cannon-loaded and modified caravels for use on the high seas, or for unscrupulous individuals to capture merchant vessels and refit them. Aware of the dangers to the realm's trade, Elizabeth quietly engaged many of these pirates in a position as privateers, sea-borne mercenaries with a mission to disrupt rival trade. The Crown would grant them safe port and passage through British waters and in return it would take half of their prizes. Whilst this might seem an arrangement heavily weighted towards the Crown's benefit, Elizabeth offered infamous pirates such as Francis Drake (Sir Francis Drake, after he made the Crown enough money) something otherwise unavailable; a safe retirement, free from prosecution, once their fortunes had been made.

[Privateers are sexy. They have limits; once your rivals develop Chemistry and Astronomy they can field Frigates, the Privateer-killer, but whilst you have a tech lead they are god-like. Privateers are, in essence, double-strength caravels with the move of galleons. They can fight, pillage and blockade, but they have one special bonus; they fly no colours. Privateers have hidden nationality, so they allow you to ruin the shipping and lives of your rivals without declaring war and without providing them a pretext for war.

Let's talk about piracy. Now, pillaging is straightforward; sit your ship atop a worker-boat worked resource such as fish or whales and click pillage. Boom, resource harvested, bit of bonus gold. Nice. Blockading is rather more fun. A ship set to blockade will create a 'bubble' of piracy seven tiles wide around it (i.e. three tiles away from the ship, plus the ship itself). This bubble, if it covers all the coastal squares away from a port, will kill all the trade from that port. This is to say that it breaks any outgoing trade routes. But wait, there's more! Not only does it deny them sea trade from a port, it denies them any trade whatsoever. Even land routes to their own connected cities aren't possible because of the devastation your ships are wreaking. Furthermore, you get a small cut (maybe 20%) of the gold they would have made in trade as a result of the piracy. Blockading three cities, we're making 11 gold a turn, easily enough to cover the maintenance costs of the privateers. But wait, there's more! Blockaded tiles also stop tiles being worked, so not only will you kill a port's trade you can quite literally kill the city this way as well.]

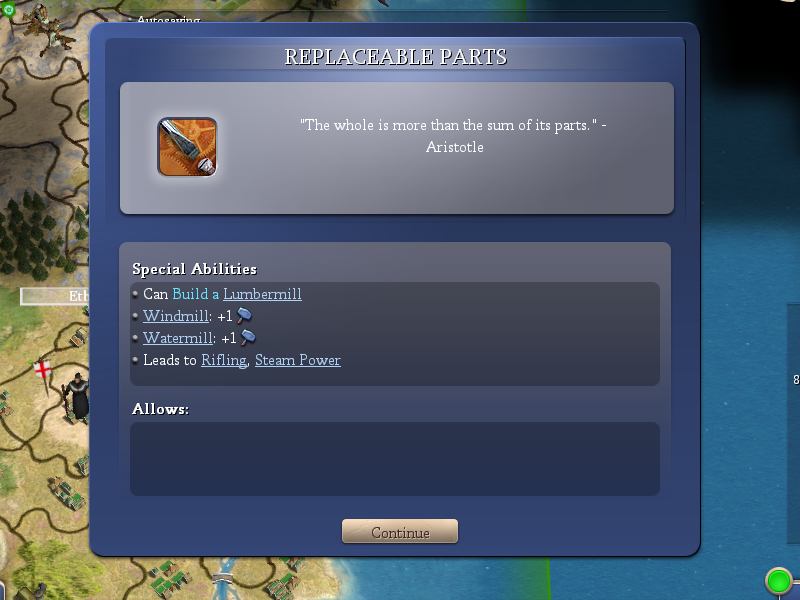

The creation of the printing press had changed the standards for production of machinery within the United Kingdom. Complex machines comprised of hundreds or thousands of individual parts had become practical and desirable, creating pressure upon artisans for greater and greater precision engineering. With manufacturing methods capable of producing parts with precision of up to one hundredth of an inch, it became possible to set precise, reliable standards for machine parts, which is exactly what the Camelot Guild of Ironmongers did in 1386. The Guild released a paper laying out the precise measurements, dimensions and materials to be used for specific parts by their members, such that these standardised parts could be used to fix broken machines without the need to completely disassemble and rebuild or repair machines from scratch. This became particularly welcome amongst the musketeers of the Royal Guard, who frequently had jams and other problems with their equipment, and the fine machining permitted the construction of large-scale sawmills with rotary blades, greatly enhancing the logging industry which until now had depended chiefly upon peasant woodcutters. Now it could meet the demands of the paper industry, spurred on by the printing press.

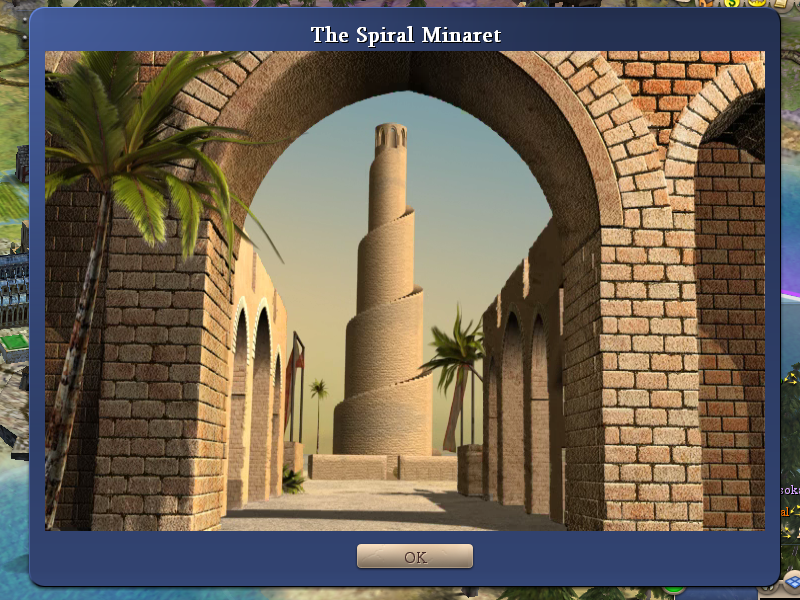

In 1396, taking inspiration from the minarets of Islamic mosques in Ethiopia, a spiral tower was built opposite Notre Dame in Delhi, with a high cupola for a priest to call worshippers to prayer. For a time, the Spiral Minaret held the distinction of being the largest structure in the world, attracting large numbers of pilgrims and inspiring similar structures at temples the world over.

The turn of the century brought good fortune to Britain and ill fates to Ethiopia, along with the winds of change. The printing press had permitted the dissemination of ideas across the realm, granting yet more power to the middle classes and encouraging freer thought than had previously been permitted or possible thanks to the intervention of the nobility. The ideas of liberalism spread, particularly amongst the wealthy and educated "Commons" of Parliament and there came a growing belief that government existed to serve the people, rather than the monarch or the oligarchy in power. These ideas of free thought encouraged invention and industry, resulting in key advancements in logistics and design - including the development of the rifle.

In contrast to the smoothbore musket, rifles possessed rifling (surprisingly), a cyclical groove running down the barrel which caused the bullet to spin during flight, resulting in a much more accurate shot than that achieved with the rifle - and consequently a further range as well. The elderly Queen Elizabeth, who had profited greatly from her policy of supporting piracy (to the point where every Ethiopian port was crippled by attacks on their trade lanes by 1400), ordered a major refit of the traditional British forces to comply with her designs for a New Model Army. At great expense, regiments as old as Rommel's Relief and even regiments which still held strong familial ties such as the Atrebates (the surname Bates was particularly profilic in that army) were re-trained and equipped to use the weapon of the modern age.

Well-understood were the military ramifications of the rifle, but Queen Elizabeth was skilled enough to use her army for diplomatic maneouvring as well. Cowed by the might of an army and alliance of states that vastly out-paced their own, the Mansa of Mali, Mansa Musa, came to London at the head of a golden train, followed by thousands of servants, courtiers and extravagant but hopelessly out-dated ceremonial soldiers. Musa made a gift of four hundred and fifty pounds of Malinese silver to the British monarch, humbly requesting her protection against the dangers that Sumer presented. He bent the knee to Elizabeth and she accepted his fealty; he arose Duke Musa of Mali.

Queen Elizabeth Pendragon died in June 1411, succeeded by her son Arthur. Elizabeth was interred in a tomb of her own devising, based upon the classical mausoleums of India; the Taj Mahal, a magnificent palace of white marble designed to house her body and that of her spouse, Prince Consort Sanjay of Bombay. The marriage being matrilineal, young Arthur was born into the House of Pendragon. Guided by his father and careful management of Parliament and the politics of the realm, Arthur did his best to rule fairly and justly in the Confucian fashion. There is something to be said about the fact that, by all accounts, he succeeded - if one does not consider his continual support of state-funded piracy.

The great wealth and prosperity that stemmed from Arthur's competent rule (and possibly large amounts of stolen Ethiopian booty) spurred on the wheels of finance, especially given the extensive series of stock exchanges around Britain. A scholarly approa ch was taken to the field of economics, attempting to understand formally the transfer and use of wealth. Milton Keynes, a descendant of John Maynard Keynes, posited the idea of a "laissez-faire" economy. By keeping the government from interfering with independent trade and business, and indeed actively implementing rules to safeguard the freedom of trade from state intervention, Britain could achieve significantly more wealth from trade with other nations. Arthur's government adopted the policy to great acclaim and for a time it did indeed produce great wealth for the nation.

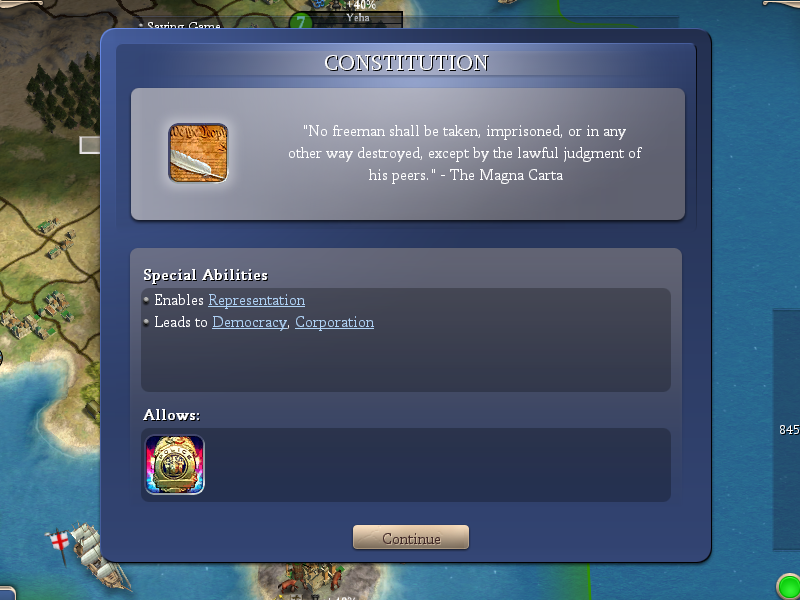

In 1429, the University engaged in a formal restructuring, dismissing many of the now outdated 'colleges' under single tutors and embracing a holistic approach, as per Merit Ptah's example two hundred years prior. The different colleges came to specialise not by their masters but instead in the different bodies of study; Uther's College today is still known for the quality of its legal graduates, as Grey's is for its doctors. This restructuring also resulted in a formal collation of the many and variegated laws and legal codes that had been established in the past thousand years of British history. Together, this body of law formed the British constitution; the laws and agreements by which the country was run, guaranteeing and safeguarding rights and privileges for both citizens and rulers.

The throne room. ARTHUR is seated upon the throne, in conference with CROMWELL, MERLIN and other Lords. Enter BLACKTHORN.

BLACKTHORN: My liege, may I present his highness, Prince Zara IV of Ethiopia.

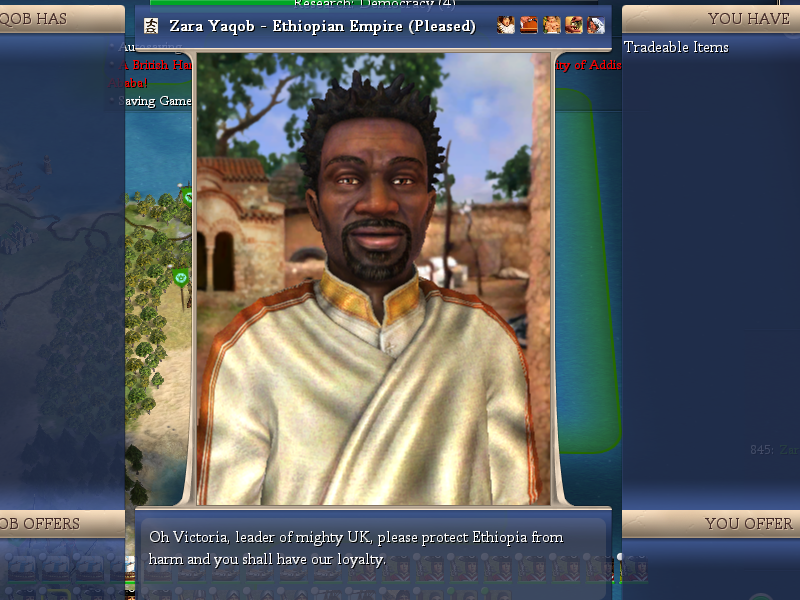

Enter YAQOB, Attendants.

YAQOB: Your majesty.

ARTHUR: Your highness. I had thought to speak with your emissary.

YAQOB: This is no matter for emissaries. I have come on behalf of Ethiopia to seek the protection of the United Kingdom. Sumer grows in strength, Mali has already cowed to you, and the American states are distant and weak. To stand with you is strength, to stand against you is folly. I know well that Confucius desired Victory's word to cover the world, and that he spoke of a 'manifest destiny' for the Confucian state; a realm that would encompass all the world in Victory's glory. Let us join with you and aid the coming of this new world; as servants, not as slaves.

CROMWELL: An excellent offer, my liege, and most sensible. Think of Confucius' plan! One step closer would we come, and not a drop of blood shed. I can find no objection to such a union.

ARTHUR: And what of you, alchemist?

MERLIN: Annabelle Fring. Jane Grand. Lord Crossley and his sons.

YAQOB: Who are these people of which you speak?

MERLIN: But a handful of those who died at the hands of your people. Have you forgotten London? Have you forgotten Cardiff? Tens of thousands died at the stroke of your poison.

YAQOB: Have you forgotten the hundreds of thousands who died in your revenge, or the million who have passed in the last sixty years, starved by the pirates who pillage our grain, who steal the very food from our mouths?

CROMWELL: We can hardly be held responsible for the actions of a few criminals you are incapable of handling yourself.

YAQOB: [Laughs.] A few? An organised assault that has been maintained for decades, bleeding our people dry. And you dare to claim you have no part?

CROMWELL: Name one piece of evidence. You will find none.

YAQOB: Is this how it must be, then? Revenge, again and again and again until we are both broken? This is a chance to break the cycle, Arthur, a chance for our peoples to live in harmony. Let us have peace, or else we must have war.

- The Grey Prince,

Malcolm Irving

Despite the dramatic portrayal of events in Irving's The Grey Prince

, which also heavily condenses events with little regard for historicity, the decision of whether to accept Ethiopian vassalage was not made on a snap judgement by King Arthur, but rather over a two week process involving argument, presentation of facts and a vote in Parliament. We know from the Parliamentary Rolls that the decision to accept vassalage then and there was voted 184 to 166 for acceptance. It seems that the primary arguments against the decision were based on long historical suspicion of the Ethiopians, fears of betrayal from a subject state and a simple acknowledgement of the fact that it would be both possible and not wholly inconvenient to invade Ethiopia, especially in its weakened state; the arguments for included an appeal to common sense (why fight for what can be given voluntarily), other concerns (the growing power of Sumer, the Americas) and the desire to end centuries of mutual strife. The casting votes were made by a small minority party with deeply Confucian beliefs, who considered the offer to be a sign from Victory, one not easily to be ignored. With the assent of Parliament, in 1434 King Arthur accepted Ethiopia's fealty. Prince Zara Yaqob bent the knee before him and arose Duke Zara of Ethiopia.

The piracy of the previous sixty years had taken a devastating toll on the population and economy of Ethiopia. The long term privateering had not only crippled the lucrative overseas commodity trade, but all maritime trades, even on the level of fishing and whelking; cockle pickers on the Aksum Bay had to fear cannon shot if they were caught out doing their trade. The bustling city of Lalibela, dependent almost entirely upon the sea for food and trade, dried up until it was a broken village of no more than a thousand souls. Aksum, jewel of Ethiopia, fell from approximately five million residents to a mere one and a half million. Very few of these reductions were due to actual murder on the part of the pirates (although there was certainly plenty of that) but rather death by starvation, sickness, violence resulting from the many food riots, and in a majority of cases simply packing up and leaving for a city with food. Not at all coincidentally, London, Cardiff and Edinburgh experienced a population boom at the same time.

With Zara's vassalage, their problems with piracy began to disappear overnight, culminating in an almost certainly staged 'battle' between the Royal Navy and the privateers, resulting in their being chased off for good. British suzerainty meant great freedom of traffic and ideas; unfortunately so in the case of Addis Ababa, which grew heavily with British immigrants to replace those fled from years of piracy, bringing their culture and ideas with them. British sympathies grew to the point where there began to be serious considerations of defecting to direct British rule.

By the end of his life in 1443, Arthur had ruled fairly and wisely, but more than that he had engineered social change across the whole of the United Kingdom. He and his two most trusted councillors, Thomas Cromwell and the Welsh alchemist Merlin (noted for his contributions to the University), had employed political reform through Parliament and social reform through propaganda made possible by the wide dissemination of pamphlets from the printing press. Most of these reforms worked to overturn the changes made by Picasso, six centuries prior.

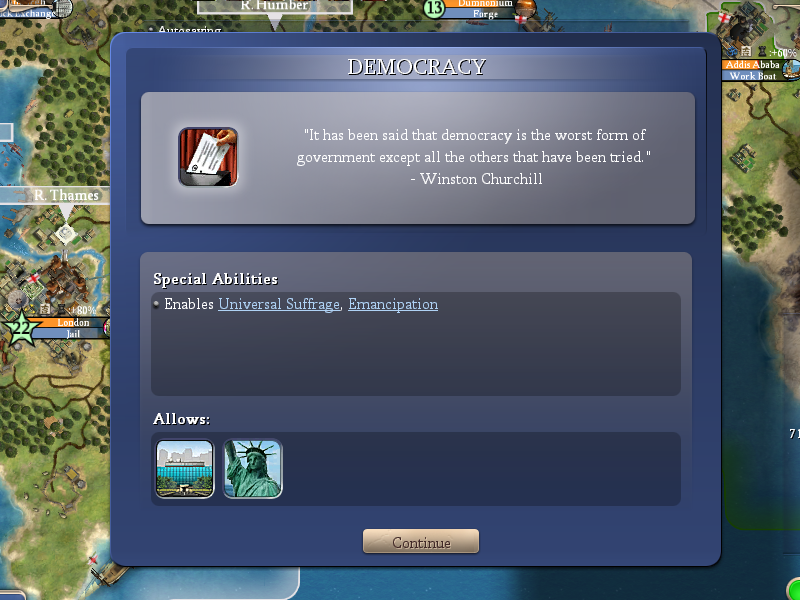

A series of small but critical changes to the law had abolished many of the legal quirks set up by Picasso centuries before, quirks that concentrated power amongst the middle classes whilst simultaneously denying upwards mobility. Arthur was a staunch meritocrat and believed that anyone, rich or poor, British or foreign, deserved the chance to rise if their talents deserved it. This emancipation from the rigid class system, from the old forms of serfdom and from the slavery of other nations, resulted in great movement of the poor towards the towns surrounding the great cities, swelling their ranks. They also inspired envy in those nations where their citizens were not so free. The reduction in power for the middle classes did result in many shake-ups of the established professional classes, and the reduction in freely avaiable cheap labour harmed certain sectors of industry as well.

Culturally, Arthur worked to break Britain's reliance on the civil service, again an institution brought about by Picasso. He weakened the political power of many officials, limiting their mandate to local government and advisory roles. In lieu of an administrative ruling class, Arthur's propaganda efforts solidified the formerly nebulous ideals of a British 'nation', a kingdom held together by the distinct, unique voices of its inhabitants. He promoted officers and engaged civil servants and administrators whose ideology matched that of the state, more concerned with promoting a lasting unity amongst his people than bureaucratic efficiency. By the time of his death, the civil service had been crippled, resulting in a massive loss of wealth and industry in London that the civil servants had engendered. Similarly, the nationalist ideals created an ongoing distrust of other nations. However, heavy cuts on red tape resulted in massive savings to the Treasury (somewhat negated by the loss of wealth in London), a strong sense of unity aiding in the internal security of the realm and a strong militaristic ethos to support the nation's security.

[Last turn of the Golden Age, so we're jigging up the civics again. Now running Universal Suffrage (gold rush, town hammers), Nationhood (no upkeep, can draft, bonus happiness from barracks), Emancipation (double growth for cottages, unhappiness for every other civ in the game, ha ha!), Free Trade (bonus trade routes) and Organised Religion (build bonuses). After this, we're taking the plunge into the Industrial Revolution...]

Author

Topic: Civ IV - Let's Try the British Empire: The Industrial Revolution (Read 17093 times)

Author

Topic: Civ IV - Let's Try the British Empire: The Industrial Revolution (Read 17093 times)