So, from about 1750 to 1850 the developments in naval technology were pretty minor. To wit: this is HMS

Victory, launched in 1765:

This is HMS

Queen, launched about 75 years later:

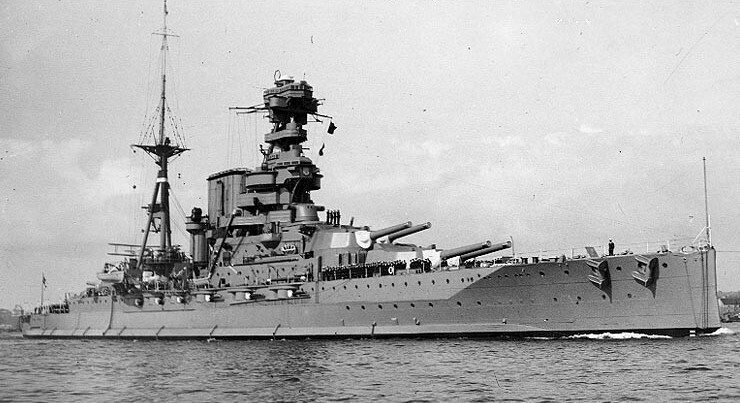

Fast-forward another 75 years, and you get HMS

Barham:

This isn't to say that naval architecture wasn't advancing between 1765 and 1840, but 1840 to 1915 saw a ton of major technological advances. In no particular order...

Steam propulsion. In the 1840s and 1850s, navies all the world over experimented with steam-powered ships, at first in conjunction with sails and eventually without sails at all. The marine propeller became a thing at this time; you see a lot of 'converted to screw 1854' and such in lists of Royal Navy ships on Wikipedia. Freeing ships from the wind greatly enhanced the all-angle maneuverability of warships, and it let naval architects move the vulnerable propulsion systems from giant poles sticking up above the ship down into the depths of the well-protected hull.

Which segues neatly into ironclads and iron hulls. These came about in the 1850s and 1860s, and made wooden warships basically obsolete (for obvious reasons).

Exploding shells were hardly a new invention, and they were used in naval combat at least as far back as the Napoleonic Wars, fired at high angles from mortar-equipped bomb ships. (...from which your bombs bursting in air, as referenced in the Star-Spangled banner, were fired.) In the 1820s, a Frenchman by the name of Henri-Joseph Paixhains first suggested the use of exploding shells in flat-trajectory naval guns. It wasn't until the 1840s and 1850s that they were cast and proven in battle, at which point the navies of the world were all, "Why weren't we doing this before?"

On the topic of naval artillery, the breech-loading gun came into common use in the 1860s and 1870s thanks to the invention of the interrupted screw, which was an important factor in the development of turret- and swivel-mounted guns atop the hull, rather than broadside guns firing from within--guns could be made long-barreled without making reloading difficult. The interrupted screw answered that perennial question regarding breech-loading weapons: "How do we keep the breech from flying out the back of the gun?" (The recoilless rifle, a later development without naval implications, answered that question with a philosophical, "Why even bother?") It was simply a breech block, threaded for a quarter of its circumference on the top and a quarter on the bottom, and a breech, threaded for a quarter of its circumference on the left and a quarter on the right. The threads wouldn't engage when the breech block was inserted, and then just a quarter-turn would lock the threads together and, y'know, not kill all the gunners when the gun was fired.

So all of that set the stage for one of those classic battles in military history, Weapons vs. Armor. Up until the 1890s, Armor had the upper hand. Naval guns were powered by black powder, a low-pressure propellant incapable of generating muzzle velocities that could scare a well-armored battleship. Research into alternative methods of sinking iron- and steel-armored warships turned up such armaments as the ram bow, which contributed to several incidents in which accidental rammings sank friendly ships but never actually sank an enemy, and the torpedo, which conversely sank enemies much more frequently than friendlies. The navies of the world developed quick-firing artillery to deal with fast torpedo boats and steam rams, and in doing so, they established the pre-dreadnought pattern: the standard sort of battleship that would persist from about 1880 to 1905.

The pre-dreadnought carried two or four (or rarely, three) main guns in turrets fore and aft, of calibers between about 11 and 16 inches. This was her armament for engagements against heavily-armored targets; they couldn't hope to penetrate the armor of the day with high muzzle velocity, so naval architects just made the guns bigger. They also carried heavy secondary batteries in the six-inch to nine-inch range, mounted singly on the port and starboard edges of the ship, with the bridge and funnels in between the port and starboard batteries.

Even with all of these advancements, a sea battle in 1885 would have been recognizable to an admiral of 1805. Two fleets would sight each other (visually), run signal flags up the masts to get themselves into an ordered line of battle, and then they would close to a range of no more than a few thousand yards (fewer than two nautical miles) and pot away at each other until one side exploded, sank, exploded and sank, surrendered, or ran. Two developments were missing before things would really change.

The first was smokeless powder. The British developed cordite in 1889, and to their credit, they immediately saw the naval applications. Guns using cordite could fire a heavier shell further at a higher velocity, and that began to tilt the balance back toward weaponry. Heavier armor-piercing shells could be fired from guns of the same size, and those shells could reasonably be expected to penetrate an enemy's armor at longer and longer ranges.

The second was fire control. In the years leading up to the First World War, naval technologists wondered if they could use their new, higher-muzzle-velocity, longer-range guns from further apart, and so fire control systems were born. Few auxiliaries had anything but local control, each gun crew laying its own gun, firing at its own pace, and observing the fall of its own shot, as God and Nelson intended, but this wasn't conducive to scoring hits at longer ranges. Destroyers increasingly had optical rangefinders of some flavor, and that left the gun crews with only change-in-range and crossing speed to take into account. Cruisers typically had rangefinders and centrally-fired guns; the fire control officers would tell the gunners how to lay their guns and then trigger a salvo. Rather than watching for individual shell splashes, they could watch for the splashes from the salvo and instruct all the guns to correct their aim accordingly. The final development in fire control systems in the First World War era was the fire director, which was little more than slightly more complicated, automated central firing. An analog fire control computer would continuously update a solution for a target at a given bearing, range, and speed, and the gun crews would lay their guns according to indicators in their turrets fed by the fire control computer. The fire control officers could order a salvo in confidence that all of their guns were working from the same firing solution, and so combat ranges were inflated five or ten times.

Fire director systems featured mainly on dreadnoughts, and I can finally get around to defining that term. Taking all of the improvements above into mind, a British admiral (and First Sea Lord, too) by the name of John "Jackie" Fisher commissioned a study on a battleship armed with a uniform main battery of ten twelve-inch guns, along with the first steam turbines to be installed in a warship. The result was HMS

Dreadnought, such a revolutionary vessel that she rendered every prior battleship instantly obsolete (and indeed, all those older battleships were called 'pre-dreadnoughts'). Not only could she deliver double or triple the firepower at maximum range that a pre-dreadnought could, she was also faster by four to six knots. Her construction sparked a naval arms race around the world (a contributing factor in the web of alliances that made the First World War a world war); a nation's naval power was measured solely in terms of its fleet of dreadnoughts, and by 1914, pre-dreadnoughts were relegated to quieter theaters.

Author

Topic: Heil dir im Siegerkranz: Steam and Iron in the Baltic Sea (Read 12918 times)

Author

Topic: Heil dir im Siegerkranz: Steam and Iron in the Baltic Sea (Read 12918 times)