Urai Culouch - 754 BC A trader at work - An image of a trader such as Urai Culouch with servants.

A trader at work - An image of a trader such as Urai Culouch with servants.I spit out the mouthful of date onto the street. Bad purchase, bad waste of copper. Maybe I will pass on the rest of the bag to the slaves as a gift. Malinense dates, pfah! Fatter than Ucran dates, but do they keep for the journey? No.

I glance at another stall selling Drunish and Mayan jewellery. Gold again. Everybody seems to have gold these days. A ring's trollhead design pleases my eye and I barter some of the dates and a couple of slips of copper for it - no doubt it will please my wife better than the dates. I find myself a little impatient waiting for the merchant to weigh up the copper. He apologises for taking longer than usual; some Egyptian traders have been cutting slips with lead of late. We exchange a few words about it; one cannot trust Jews; and part company before he tries one of the dates.

The market is more crowded than ever; so many people, too little space in the street. In my father's time there was a field we could sell wares upon by the river, but the temple's skeleton stands there now, waiting for marble skin to climb the supports. They say it will be finished in a few years' time and we shall finally meditate upon Buddha's teachings in a sacred place. Perhaps; always I am hearing of delays in construction. There are more and more Malinese monks around the temple site these days, praying and meditating. One of my suppliers tells me that the Oracle's priests have made their way across the coast to Mali and there they practice Buddha's teachings much the same way.

I squeeze past a cart and donkey, closing my nose to the sharp stench of the fishmonger's stall until I reach my own. The copper delivery is late, but so am I. The wagon forces its way through the traffic a handful of minutes after I arrive and I take the opportunity to harangue the waggoner over his delay. Not that it matters too much. Duroch copper is plentiful down here, even at what I bargain it for, and of course there are a few foreign imports. Poor grade metal, impure. Would not trust it.

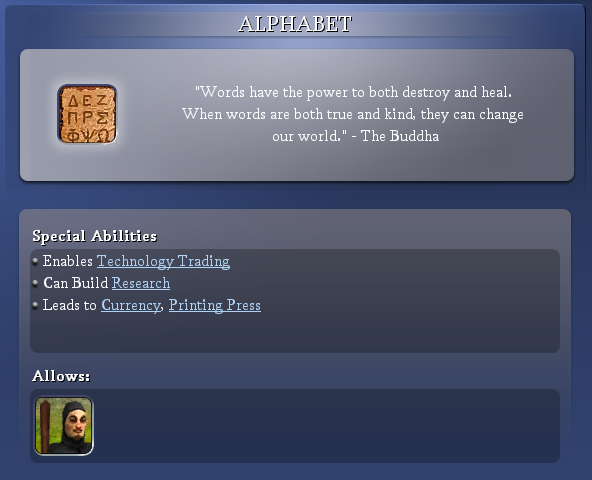

I check the tablets of sale; a mess of Egyptian, Mayan, Malinese and Ucran scripts as usual. One or two words are unfamiliar; I mouth the letters until I get the sound right. Most of the words I know from business or tax, as the taxman's receipts are often written in the new alphabet.

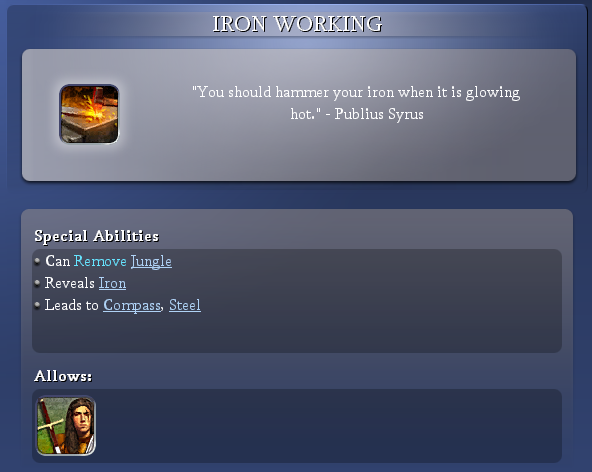

Morning trade is slow; small traders picking up copper slips for trade and depositing grain, fish, whatever goods they have. A few of my usual clients are here, a smith, a beater, a jeweller. They take their orders in exchange for the usual goods - or so I expect. Today the smith, David, gives me a dagger not of bronze but of bright silvery iron. I test the blade and argue it will not hold as well; he gives me a small working knife in compensation, again iron.

We break whilst the workmen have their mid-day meal and I leave the wagon with my guard. I walk to David's forge and ask him about the iron; why forge such an inferior metal? He tells me that he knows some Malinese smelters in Druna able to get iron from local ore very cheaply, and the ore is more abundant than copper.

I thank David for his time and for lunch and return to my stall, my mind burning with thoughts. If Drunish iron is so common and so easy to work and smelt, would it not serve me to send one of my sons there with slaves to dig out a new mine? Perhaps. When Seth arrives from Duroch, we will discuss the matter. Until then I settle back by my stall, calling out my wares under the baking Ucran sun.

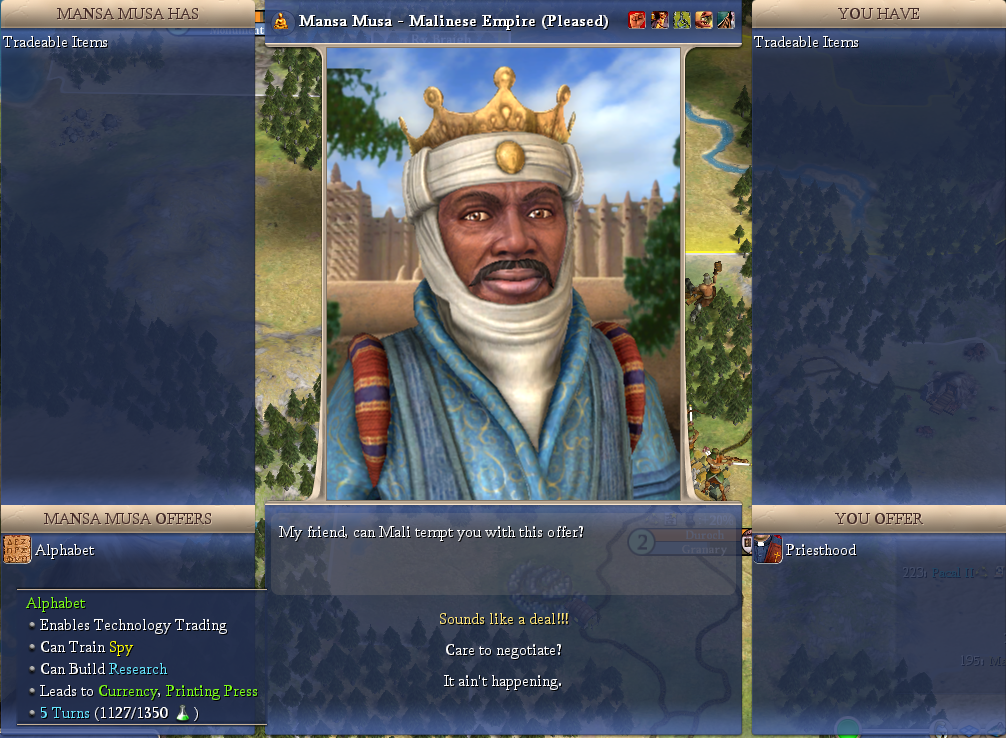

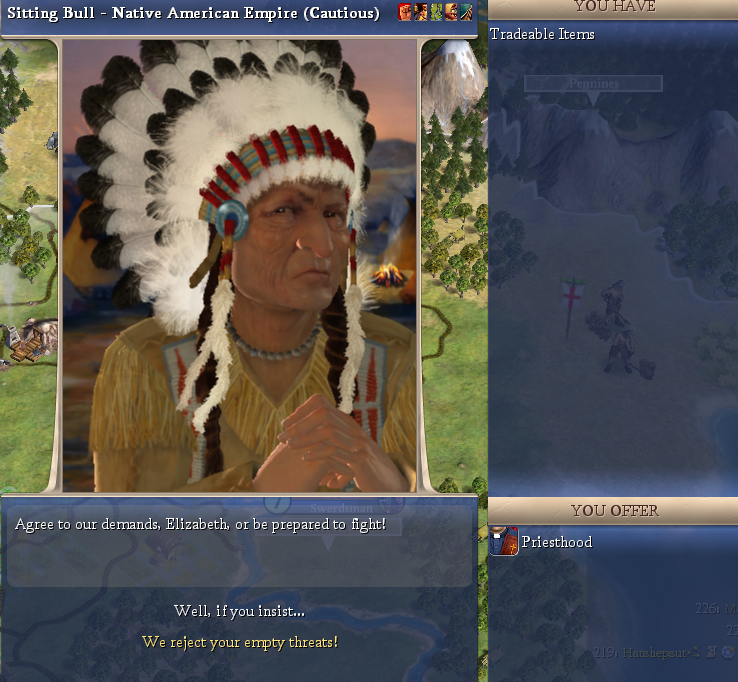

Mansa Musa researched Alphabet a little before us, so he offered to trade it for the priesthood. Since we were only 5 turns from researching it ourselves, I got him to swap iron working for priesthood and monotheism. Puts him a little ahead in the tech race, but saves us about 18 turns of research.

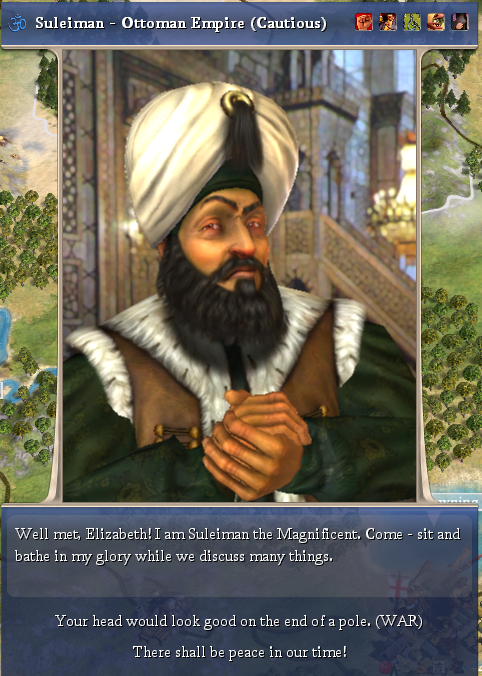

Alphabet arrives and with it the power to freely tech trade - and to build Spies to send against our enemies.

As a side note, at 770 BC we are now 273 turns into the game. Time still progresses at a rate of 1 turn/10 years.

Poor iron from the new vein, have to smelt it almost to destruction to get the slag out. Brittle. I walk along the edge of the pit, away from the bloomery to get my breath. Below me, slaves and criminals toil away at the rock with picks and chisels. I give a nod to one of the guards as I pass him, then head to the small adobe building where the quarry records are kept.

I settle down in a chair and open the records chest; the cool, dark chest keeps the wax within from melting. I pick up my stylus and spend some time working on the accounts, then push them to one side in favour of letters.

Ada informs me that Elijah is well and teething. She will bring him down to Druna next year to meet me. I spare a moment to smile at my latest son's health and pour out a little beer in celebration - and because I am thirsty. I wish I could have seen his birth, but all my sons are too young for the business and my brother must manage the copper mine back home.

The road will help. My father would tell me about the long road:

"Your grandfather's legacy," he would say. "When your great, great uncle began mining here in Druna he wanted to keep both parts of the business together, to bring the copper and the forgers from Duroch and send the profits and goods of the business back home without having to pay the tolls and tarriffs of the Ucrans."

At first it was just a dirt path, trodden by caravans my great, great uncle paid to make the dangerous journey. Then over a hundred years our family dredged out the marshland, raised the road with stone and gravel and paved it, easing the path of the traders between both towns. My grandfather himself laid the last stone, linking the two cities together.

I turn to the next letter. Orders for more iron from the Drunish king. Production orders too; breastplates, greaves, axes. Or perhaps not axes. With bronze we could only afford an axe blade for the scarcity of the metal, but a longer blade could be affordable with iron. One of the weaponsmiths has shown me a long axe with a short handle, akin to a spear but all in metal and with one sharpened edge like a sickle. It strikes me that such a weapon might take months more training than an axe or spear, but manages to combine the cutting power of the former with the reach of the latter.

I will present the weapon as a gift to the king, for I know a man who can use it. Goliath, the king's champion, is most skilled in both the axe and spear. If I approach him first he might well be able to make use of it; I understand he has taken to training young soldiers in his house and grounds. Perhaps this would be a good place to reach him. I will send my assistant, Cain, out for the city at the end of the week.

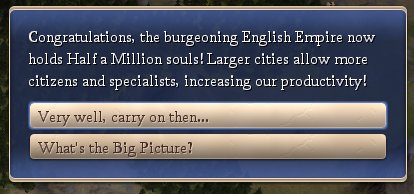

In 650 BC, there were half a million souls culturally Ucran or Durochite.

In 650 BC, there were half a million souls culturally Ucran or Durochite. In 620 BC, iron mining reached full capacity at Druna. A road was built between Druna and Duroch.

In 620 BC, iron mining reached full capacity at Druna. A road was built between Druna and Duroch. In 590 BC, a barracks was built in Druna. A large order for iron swords and armour was placed by the king.

In 590 BC, a barracks was built in Druna. A large order for iron swords and armour was placed by the king.Lilith waits for me in the courtyard. Oh, to think that I should not see her for seven long months! I straighten my breastplate and cloak, sliding my sword in and out of its scabbard as long practised at Goliath's Green. Satisfied, I take the money pouch at my neck and finger the treasure within; still safe, still where I left it. I put my helmet under one arm and rush out to meet her.

She is wearing a white shift, cotton and woven with crossing brown patterns. It gleams in the moonlight, which flickers on the pool by which she sits. She is facing away from me, so I sneak up behind her and put a hand over her eyes. She gasps, then giggles once she realises. She pulls my hand away, stands and kisses me. The soft touch of her lips runs through my blood, twinged with regret. The embrace ends and she looks up at me with bright doe eyes. Around her neck I see her necklace, an ivory charm on a golden chain.

"How long?" she asks.

"A few hours, perhaps less," I say.

"You go that soon?"

"Sem Na commands it. I cannot go against the king of kings' command."

Lilith snorts. "He is only that king's son. I do not like him."

"It will not be long, I promise. I must serve our king, and our king commands I serve that one. Come now, let us talk of other things."

We embrace again. Time passes. I become aware of the light filtering over the horizon; dawn is coming. I stir, trying not to wake her. She wakes anyway and smiles at me, a fresh touch of sadness to her eye.

"Before you go," she says, "take this to remember me."

She takes the necklace from around her neck and places it around mine. I hold her hand to my chest for a moment. I reach for my purse and take out the treasure within; a golden ring, its face engraved with an image in a style two centuries past.

"Take this also," I say. "It belonged to my mother, and to her mother, and so on as far as our family can remember. Take it to remember me-" and here I kiss her hand "-for when I return, we will be married."

She holds me tightly, so tightly the air is pushed from my chest. I feel the touch of tears on my shoulder, and also running down my face.

"Yes," she whispers. "I give you my heart, Ben. What is mine is yours, what is yours, mine."

We kiss again, a final time, and it tears my heart to part from her. We do part, though, and say our farewells. I take up my sword and armour and rush to meet the priests.

Benjamin Cullock - 551 BCThe priests are busy arguing. The Sioux priests are demanding the Oracle's men come with them without their guard, to 'teach them their ways'. Our priests are insisting they will not go further without us escorting them. The Sioux aren't even Buddhists, they just want to ape the Oracle's temples so they can con their people into believing in false gods.

It is late. The Sioux priests are asking for a night to consider the matter, which our own priests are more than willing to agree to. We all need sleep, though having first watch I envy the priests for getting a little more of it.

--~o~--

I wake up, drowsy. It is still night out, but something is gnawing at my nerves. I shake myself a little more awake and reach for the jug of water by my bedroll.

There is a rustle outside, different to the leaves moving in the wind.

I stop reaching for the water and instead move to take the scabbard by my bed with one hand, then the other. I inch the blade slightly out of the sheathe, ears pricked.

A series of quick, light thumps, then a heavy one as something wet hits the ground.

I mutter a curse under my breath and glance at my heavy armour by the bedroll; no time to put it on. I stand, straining my ears for sound. I can see a warm glow outside from the fire, the shadow of a rock on the ground. Two shadows, one of them moving.

I leap out of the tent, screaming an alarm cry. My sword sings as it leaves the scabbard, slicing up and into the chest of the Sioux axeman as he makes a gurgled scream of his own. His torch strikes the ground and the shadows skulking around the tents come alive and let loose warcries. Some of them come for me, others try to kill as many unprepared in the tents as they can before the real melee begins.

I do my best to hold my own, but there are half a dozen of them and I lack armour. I fight for my life, swinging my scabbard like a shield and a second sword. An axe bites into my shoulder, another into my hip. I can feel blood flowing freely, my arm loses its strength and I am ready to collapse. I drop my sword and a Sioux comes to finish me.

He collapses over my body, an arrow from his back. One of the priests stands at the entrance to the tent, a shortbow in his hands. He nocks another arrow, but a Sioux axe cuts into his head and he strikes the ground. The few remaining on my side are falling quickly, though we have cut down many of them in payment.

I crawl through the mud, shifting the dead Sioux's body to one side. As it falls, its purse comes open and I see a slip of gold poke out. The gold bears an imprint; the wolf, the mark of Aradai. The mark of the king of kings.

I go as far as I can before I drag myself to my feet, hobbling through the forest until pain and exhaustion finally get the better of me. I collapse by a stream somewhere in the forest, bright lights piercing my vision as everything else fades to black. The last thing I feel is the ivory charm at my chest pressing into my skin against the ground.

--~o~--

Time has passed, I know not how much. I recall events vaguely, images and sounds and smells and touch. Hands dragged me from the shore where I lay dying, threw me into a boat. Other hands cleaned me, dressed my wounds. I felt my arm again, and it burned with pain. Heat, sweat, the marks of deep fever. By the grace of Buddha, it passed. Hands feeding me broth, water. Hands helping me up. Hands chaining my legs, my arms. Hands hurling into a cart. The glint of gold, the faint smell of metal. A Mayan fisherman selling me, his sweat bound with the oils of fish. A Mayan trader buying me, his sweat soaked with earth and sickly perfumes. The white heat of a brand in my chest, the stench of cooking flesh.

I can smell the dust in the air as I and other slaves go downriver. The barge moves slowly, and it is dark and cramped where we sit, waiting for our destinies. A mine? A field? Some king's personal aide? The pit, to fight for death and glory?

I do not know. I may never see my Lilith again. No doubt she thinks me dead, a victim of a tragic raid, or Sioux deceit. Yet one image from that chaos of violence sticks in my mind; that golden wolf, leering at me from the Sioux's purse. Was that chance? Could there have been a deeper motive?

I do not know, but I will not rest until the day I find out.

In 560 BC, arrogant demands were made by Sioux priests. They were refused.

I finish my morning meditations and review Confucius' teachings once over before prayers to Buddha. Some of my brothers do not appreciate the dual devotion, but just because I became Confucian does not mean I must abandon my Buddhist birth. I rise and move to the hearth to prepare morning meals for the other monks, as is my duty today.

I gaze up at the fine Buddhist temple close by with a slight touch of envy, then admonish myself for wrong behaviour. The monastery will take a lifetime to complete, so for now we make do with our simple shacks as the slaves work at its construction around us. An unhappy people, but such is their lot in life; this is the punishment for those who ignore Confucius' guidance and break the law. I spare a moment to watch the naked men work, lifting stone and breaking it at the mason's directions.

One of the slaves stands out, muscled like the rest but not of Mayan or Egyptian descent. A Durochite I would guess, but heavily tanned from his labour. A criminal, no doubt. What strikes me is the number of brands on his chest and arms; a slave who has tried to escape or has started fights many times. Why he has not been killed escapes me, but the lines on his face and the slightly sagging muscles tell of long service. He is not completely naked either; he wears an ivory charm on a leather thong around his neck.

As I watch, meditating upon their just punishments, one of the guards spits at the necklace -wearing slave. The slave grows still, his muscles bunching up. A moment later, he continues working. The guard spits again and laughs. The slave turns to face him. The guard walks up and slaps the slave, shouting at him. The slave remains immobile, even as the welts appear on his face. Then the guard grabs the slave's necklace.

"No slave should own such a-" begins the guard.

He does not finish. The slave's fist strikes him just beneath the ribs and he doubles over. The slave tears the necklace out of the guard's hand. Other guards draw long knives and clubs and move to descend upon the slave; they have had enough. The slave stares down at the guard with a cold, hard eye, as if deciding whether that man should live or die.

"Halt!" I cry. I run down to the working pit, holding up my purse.

"This slave is trying to escape," says one of the guards. "The Maya might have let him get away with that, but we won't. Come, slave! A quick death, or a slow one?"

The slave takes the club from the fallen guard's belt and readies himself, as if to take on all the half dozen guards at once. I throw myself between him and the rest, pulling a handful of gold slips out of the bag.

"Wait, I will buy him!"

The guards pause. The one who spoke before purses his lips.

"Not ours to sell. King's labour." The guard glances at his comrade on the floor, then at the slave, then at me. "This slave has to die, holy one. But I suppose we could accept payment if you wanted to take him away from here and do the honour yourself."

I pay the bribe and order the slave to hand over his weapon. The slave reluctantly does so. We leave the site to the glares of the guardsmen, bringing the slave to the camp where the other monks wait. We reach my tent and he speaks to me.

"I will escape," he tells me in a calm but resigned voice. "I do not want to have to kill you, monk."

"You are but receiving just punishment for your crimes, slave. Even so, I take pity on your plight. There are better lives for a slave; you could be a body slave, or with your strength a guard. Lives with comfort, with luxury."

"But not with freedom."

"No." I shake my head and take the basin of water I use for washing. I wet a cloth and raise it to clean the slave's face. He grabs my wrist; a little more pressure and my bones will snap.

"I told you, monk," he growls. "I will escape, even if I have to-"

The slave stops. He squints, peers at my face for the first time and his grip loosens.

"Cain?" he asks. He shakes his head, the confusion fading from his brow. "No, of course not. He would be dead by now."

"What are you talking about? How do you know my name?" I shake my wrist free of the man's grip, taking a step towards the exit.

"Are you- Did you have a father named Aaron Cain?"

"That was my grandfather's name. Why do you ask?"

"Your grandfather, was he a servant? A servant to a rich man by the name of Cullock?"

"Well yes, if you must know. The Cullocks were kind to my family, when they still lived. My grandfather would speak of them often."

"When they lived?" The slave's eyes harshen with fear and anger. He raises his voice. "What do you mean? What happened to them?"

"Confucius beyond! Who in the Buddha's name are you, slave? Who are you that dares speak so to your betters, and how do you know my grandfather?"

The slave's eyes grow less angry, but no softer. He stares at me as he did the guard, as if he alone could choose if I lived or died. When he speaks, his voice is a hoarse whisper.

"My name is Benjamin Cullock."

I swear ingraciously at the slave. "That is nonsense. Benjamin Cullock died before I was born." The slave growls, but calms himself and speaks in a clear, level tone.

"He did not die in that forest, though he was betrayed and left to die. He was saved and sold, and worked in a mine for twenty five years before he tried one too many times to escape and they tried to drown him. He escaped again, and got caught again in Aradai, then was sent along to Ucra to break stones until his life wore out."

The slave sighs. "I can see you cannot believe me. Who would? Did your grandfather ever mention a ring? A golden ring, worth the world to the family he served?"

"He did."

"Aradai gold, sent to Druna and wrought into shape, then back along those roads to Ucra. Not a large ring, just large enough to fit a woman's finger. Not the finest or most precious of rings, but fine enough to be fine. It had no stone but upon its surface there was an old design, a horned beast in the shape of a man; a troll of old. On the back of that design were two initials, those of my ancestor Urai Cullock. I know this because my mother wore it, and I held it before I gave it away."

I stare dumbfounded at the slave. My grandfather had but mentioned that ring once in passing, that it bore a troll's head, but I knew his story to be true through other means.

"I have seen that ring, Cullock," I say, choking a little on the name. "I have seen it on the hand of the queen."

--~o~--

Benjamin Cullock - 524 BCI am washed now and properly dressed, the marks of my years of shame well covered. The warmth of the fire soothes my skin, as does the beer Cain has given me. We spoke at length of what had become of my family, my loved ones.

A fire swept through my family's home during a great feast. My father, my brothers and sister all dead. My mother passed away not long after, my cousins struck down by harsh winters in Duroch. I thought this at first mere tragedy, but then I learned of the owner of my clan's former estate; Sem Na, king of kings. Husband to Lilith of Druna.

When Cain told me this, I gripped the mug of beer so hard it cracked. Just thinking of this makes my heart burn. I keep trying to tell myself that it has just been a series of accidents, but everything is too neat, too convenient. It cannot have been coincidence - I know that Sem Na is responsible.

I cannot stay here. Vengeance will drive me to try to kill him, and whilst this would be a most satisfying end, what will it accomplish? I cannot get past all his guards alone. Cain has agreed to help me in this. He will send me to Druna with a letter of reference from the monastery; I will arrive in Druna a celebrated warrior to teach at Goliath's Green, a false man but a free one. Perhaps there I might find peace, and if not then I can work to train soldiers fit to fight for the king.

Or just possibly against him.

In 520 BC, the Trollkin are formed, an elite unit of swordsmen specialising in urban warfare.

I never thought I would love another, but even a bitter old man's heart is not so cold. The Drunish king favours the marriage, for his daughter is both shrewish and his only child, but the young girl has taken a shine to my scars. I often did beguile her of her tears, when I did speak of some distressful stroke that my youth suffered. She gave me for my pains a world of sighs, she wished she had not heard it, yet she wished that heaven had made her such a man. She loved me for the dangers I had passed, and I loved her that she did pity them.

I told the truth of my story to the king today, to ease his worries that his daughter was marrying a man of no stature. He told me that he knew my father, in his youth, and that his iron had helped him keep order for many years. He hoped that as his son (though in truth I am older than he) I and my children might do the same thereafter.

Benjamin Cullock - 508 BCOnly six months since the old king's death and already I find myself away from home. I should stay behind to rule in his stead, but reports arrived of dangerous new men landing on the beach and I have come to investigate with my warriors. There is a ship on the coast, larger than any trade ship I have ever seen. It is moored by a small fishing village, Eed, and runners tell us they belong to a people known as the Ottomans.

I approach the ship with my bodyguard of Trollkin, men I have trained and fought with personally, men I trust with my life. To our relief the precaution seems unnecessary; the men emerging from the ship are not warriors but sailors and fishermen. Their cargo consists primarily of sealed grain, dried fish and tools. We quickly discern that we share no languages, not even Malinese, but after a great deal of miming and drawing pictures in the sand we learn that they were blown off their course by heavy winds and happened upon our shores by accident.

We perform some small trades and invite them to eat with us. The evening goes well, though since neither party shares the other's language it is quiet, at least until the singing starts. It turns out that drunken singing sounds about the same no matter what language it is in. When the meal is over, we retire to our tents and the soldiers to their ships.

--~o~--

I wake instantly and my hand goes straight to the sword beneath my pillow. I spring to my feet and my sword arm swings up and out in an arch, bringing the blade across the assassin's throat. He gurgles softly and falls to the ground. I stare at him for a few heartbeats, still as a mouse. In those heartbeats I pray to Buddha that my wife and sons are safe at home. Then I call for the guards.

My men enter the tent as I wipe the blade clean of his blood. They look at his foreign clothes, his strange knife. One of them calls to have the Ottomans arrested. I raise my hand to stop him, breathing a little more heavily than I would like. I am not as young as I was.

"Look at him," I say. "The clothes are wrong. The right style, but they don't fit. He's not the right race either, the man is clearly Ucran. I think we will find one of our guests has gone missing."

One of my men takes a closer look at the body.

"I've seen this man before," he says. "A bondsman at the court in Ucra."

I feel my gut sink.

"Then Sem Na has finally made his move against me."

I turn to my men, all of whom have gathered now. "I know you, each and every one. Many of you I trained myself, all of who have fought beside me. You know me, too. You know who I am and what I have lost. You swore an oath to me when I came to the throne, and I swore one to Sem Na, though I did it through my teeth. Now I break my oath, for he has broken his. Will you do the same to me?"

"No!" shout the men.

"Good. We march back to Druna at first light. Pack up the tent and use my purse to buy off the sailors, their crewman is almost certainly dead. Give them the body too, as proof that it wasn't our fault. When we get back you will have one day to kiss your families and prepare; after that, we go to war."

In 500 BC Ottoman sailors arrive on the Drunish coast. Trade commences immediately.

They are at the gates. Sem Na is pacing backwards and forwards in our chambers. We should have taken the escape route hours ago but he tried to wait. He waited too long; the Trollkin found it and he had to collapse the tunnel or risk them getting in. So now he paces, struggling for any answer that might save his life, his kingdom.

We are old, and our children are dead, murdered by a man I once loved. What future, what kingdom does he hope to save? What future dare I hope to have? I remember when the messenger came, when war struck the towns and we fought to repel the warriors. It failed, and all we could do was hide behind our walls and scorch the surrounding lands. That was when he revealed his true name, brought back a ghost from Sem Na's past and my own that I thought long buried. The siege is spent, the walls have surrendered and now only those blindly loyal or doomed to die will fight for us.

He is here. I cannot lie, there is a flutter in my heart when I think of him. Even after all these years, even after everything he has done, all the atrocities committed in the name of revenge, a part of me cannot hate him. A small, insignificant part, but a part nonetheless. If he found me, what would he say? Would we say anything? Could there be anything to say? I hate everything that he has done to me, yet I cannot hate him.

Sem Na has taken up his sword; a gift from the Cullocks in his youth. Does he plan to fight at last? Will he go out in the glory he never showed in life? He looks at me now and realise I have seen that look in his eyes before. I have seen it at court before the guilty criminals. I saw it when news came of our sons. The look of a man with power over life and death.

A man deciding: Live, or die?

--~o~--

Benjamin Cullock - 503 BCI strike the door with my axe and it splinters before me. No attempt has been made to barricade the door. Behind me Trollkin and Durochite axemen fall into position and gape at the scene as I do.

There is Sem Na, sword in hand. There is Lilith. Both are dead; Lilith's blood soaked around the wound in her chest, Sem Na's guts strewn where he fell upon the sword. There is silence. Seeing no threat, the axemen melt away to return to the looting. My trollkin linger until I signal for them to leave me.

I approach the easier of two terrible sights first, standing over Sem Na's body with a growing, futile rage. I spit bitter words beneath my breath.

"Sem Na, you robbed me of my life, my freedom, my wife, my home and my family. You stole everything precious from me and now, now you steal even this!"

I draw my sword and stab the corpse. It is little more than cutting meat. I let loose a scream of seventy years' rage and frustration and stab the body over and over again, tearing apart the fine royal robes it wears. When I can stab no more, when I am exhausted from desecrating this corpse I reach down and pluck the thin golden diadem from its forehead. A wolf's head scowls at me from the crest. I place it back on the old king of kings' face and make one last stroke with my sword.

It would have been appropriate if the soft gold had split in two, but iron is soft too. The diadem bends and is notched cruelly, the wolf's head disfigured but not bisected, much like the face below it. I will have it melted down to make a crown of my own.

I turn away from that broken king to view a broken queen. She is old now, we both are, but I see in her still the beauty I loved those many years ago. I touch the necklace at my neck, the gold long stolen by an envious master but the ivory still my own. The blood around her neck is disturbed by drops of salt water. I brush my hand over my eyes and take hers. Her fingers bear two rings; one opulent with pearl and sapphires, the other simple gold with a gemless face. I take back the golden ring; the blood lubricates the finger, making it easy.

I take the thong from around my neck and place the ivory charm in that hand, closing her fingers around it. I kiss her cold cheek and I whisper.

"What is yours is mine. What is mine, yours."

--~o~--

Jarod Cullock - 491 BCMy father is at rest. At his request we buried his body by my mother's side, but his heart in the grave of the old queen.

Order is all but restored. Since Ucra was pillaged and razed to the ground in my youth, Father gave control of the city to the clan of Durochite axemen that helped him take it; the Cassae. I might not have done the same, but a strong presence of the Trollkin has kept them loyal. They pay their tax, they contribute to my armies. They are vassal kings to me, no more and no less.

So too is the king of Duroch, so too the lord of Breoch, so too at last the king of Ardat - what once was Aradai. I am high king of Druna and of all the world that matters, and I do not pay service to those beneath me. I am the king of kings, not the slave of slaves, and by the Buddha, by the Oracle, by the Mandate of Heaven, my word is law.

You know something? I don't especially like writing in first person present tense after all. This just isn't a time period where I can get away with doing it epistolary.

Fun note: That whole rebellion didn't happen as a battle in game, I'm literally just adding fluff to the two turns of revolution that happen when you change a civic. In this case, changing to

Hereditary Rule. The sole benefit of Hereditary Rule is that it lets you violently suppress your own population; military units in cities create happiness.

That said, it's a decent benefit for low upkeep. Ucra's been kept small for years because it didn't have sufficient happiness to get past a certain size. That's all about to change.

Revolutions in game aren't that cool; you just spend a few turns making no production, tax or research. Revolutions in real life are rather more exciting, and we're going to see plenty of revolutions as this LP continues.

Author

Topic: Let's Play Civ 4: Beyond the Sword - The Wolf & The Troll (Read 14607 times)

Author

Topic: Let's Play Civ 4: Beyond the Sword - The Wolf & The Troll (Read 14607 times)